Gallagher's Golden Moments

Peter Gallagher, A77, on finding the real thing

by Ann Marsh

Peter Gallagher, A77, opens the front door to his Los Angeles home and greets a visitor with a wide grin. Gallagher, star of the hit Fox drama The OC and veteran of 33 feature films and more than 23 television movies, exudes a matinee-idol charisma, in spite of some well-earned laugh lines.

A classic triple threat who dances, sings, and acts, Gallagher has done it all. He debuted on stage in 1977 in a revival of Hair, and went on to star in the critically acclaimed Broadway revivals of Long Day’s Journey into Night and Guys and Dolls. In 1989, his performance as the cheating husband in Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape, put his film career on the fast track. Work followed in films such as The Player, Bob Roberts, While You Were Sleeping, and American Beauty.

Now there’s a new kind of celebrity with The OC. He plays Sandy Cohen, a father and public defender who brings a troubled teen from a poor upbringing to live with his family in the moneyed world of Orange County, California. The show, in its third season, owes its success in part to its broad appeal. “I love the fact that often both girls and their moms will say they watch the show together,” says Gallagher.

As he sinks into a comfortable chair, at ease in a crisp blue-and-white shirt and blue jeans, Gallagher is attractively open and humble. At 50, he knows how much of his success has depended on paying his dues: hard work, luck, and thoughtful script choices. And he’s quick to give Tufts credit for his early training; he turned out recently at a Beverly Hills event where the Los Angeles Tufts Alliance honored three alumni with the first P. T. Barnum Award for Excellence in Entertainment.

It wasn’t the Oscars, but that suits Gallagher just fine. Acting, he says, has nothing to do with the red carpet. It has nothing to do with fame or the Nielsen ratings, but those “golden moments in acting,” those times, he says, “when it all works.”

“For that moment there’s a palpable and powerful sense of community encouraged by great writing and all the other aspects of production,” says Gallagher. “It can be the deepest of silences, an explosion of laughter, or a shared sense of recognition when the show illuminates something true about being human.”

The Time of His Life

There was no discernible acting talent in the Gallagher genes, but there was perhaps an inborn drive to succeed. His father grew up in Pennsylvania, the son of a coal miner. “Through hard work, my grandfather’s foresight, and a lot of help from the nuns at school, he [my father] and his brothers were able to work their way through the University of Notre Dame and became the first Gallaghers in their family to work aboveground,” relates Gallagher on his official website. “It’s a tradition we strive to continue.”

Gallagher was six when the family moved from Yonkers, New York, to the rural community of Armonk, where his mother was a bacteriologist and his father was in the billboard business. He soon displayed a talent for hamming it up. He loved singing around the house and performing wasn’t too much of a stretch.

The acting bug took hold when he was in junior high. As he recalls it, “Mr. Bissell, our high school music teacher and theater director, was holding auditions for The Fantasticks and was looking for someone who could do a Cockney accent to play the part of Mortimer, “a mostly mute Indian practiced in the art of dying,” says Gallagher. “I had the strongest suspicion that maybe theater might be for me. It took three hours to build up the courage to audition. I got the part and had the time of my life.”

At Tufts, he majored in economics, but acting and singing claimed most of his free time. He took vocal classes at the New England Conservatory and sang with the Beelzebubs. He performed with Torn Ticket II, Tufts’ musical theater group, including in the first production of Follies to be staged after the original Broadway show. He also worked with the Boston Shakespeare Company.

Tufts also was where he met another love of his life. During the first week of his freshman year, Gallagher was running up the stairs of Bush Hall. Coming down the stairs was Paula Harwood, another first-year student.

“We did a double take,” Harwood remembers. “We stopped. We said hello.” Fourteen years later they married and now have two children, ages 15 and 12.

Looking back, Gallagher says Tufts was a place where his boundless creativity could flourish. “There was a certain kind of freedom that Tufts offered in terms of what you could get credit for, where you could live, and what you could do,” he says. “The freedom that was afforded to us in making choices—especially non-obvious choices—was really beneficial.” Gallagher also credits an acting class taught by Tommy Thompson. “He was terrific; he urged me, forced me into taking my own work very seriously.”

The summer before his senior year, Gallagher decided to pick up some extra credits at UC Berkeley. While there, he found himself transfixed by a Shakespeare film series. By the time he returned to Medford, he had made up his mind. “I couldn’t imagine life without theater,” he says. “I resolved to give myself six or seven years to make a living on stage.”

He caught his first break almost immediately after graduating from Tufts when he was chosen over thousands of other hopefuls at an open casting call for Hair. “I was young,” recalls Gallagher, “and being ignorant of just how impossible it was to succeed as an actor helped. I kept on showing up and not giving up.”

But before that show had even opened, he landed the Danny Zuko lead in a traveling production of Grease—joining the ranks of Treat Williams, Richard Gere, and Patrick Swayze as actors whose careers were launched by that role. He eventually made it to the Broadway company of Grease, and since then has logged nearly 2,000 performances in eight Broadway shows.

Gallagher’s Broadway highlights include playing the charismatic Sky Masterson in the Tony-winning revival of Guys and Dolls, and in 1986, earning a Tony Award nomination for his performance opposite Jack Lemmon in Long Day’s Journey into Night. He also won a Theatre World Award for the Harold Prince production of A Doll’s Life and a Clarence Derwent Award for Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing. More recently, he returned to Broadway in 2001 in a Royal National Theatre production of Noises Off and in 2002 he starred in The Exonerated, winner of the Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding Off-Broadway Play and the Lucille Lortel Award and Drama Desk Award for Unique Theatrical Experience.

|

|

| |

Roles of Surprise

Gallagher burst onto the movie screen in 1980 when he portrayed a young singer being groomed for superstardom in The Idolmaker. The film premiered at Radio City Music Hall in front of 6,000 screaming fans. Other roles followed, but it wasn’t until sex, lies, and videotape in 1989 that he again generated serious buzz. He played a morally challenged yuppie lawyer, and there was no shortage of praise for the cheating husband the New York Times’ Janet Maslin called a “sensual heel.” Six years later, Steven Soderbergh wrote the lead role in The Underneath specifically for Gallagher.

His visibility and reputation grew with films such as Robert Altman’s highly acclaimed The Player and Short Cuts, as well as Oscar winner American Beauty. His feature film credits now number more than 30; when asked for favorites, he mentions To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday (1996), based on the play by Tufts graduate student Michael Brady. He agrees that he has often played a pivotal but secondary character; in While You Were Sleeping (1995), he’s the handsome but elusive love interest of Sandra Bullock. The opportunity to be part of a creative collaboration, he says, has long guided his choice of scripts.

“It has always been more interesting to play a smaller role in a film that I really believe in with a great director, and one that will allow me and enable me to find as much dimension and surprise as I can find in the role, than to be the star in a film that’s not that special,” he reflects. “The experience of contributing to a film or show that ends up being really good is extraordinary. Conversely, there’s no worse feeling than doing something for all the wrong reasons and having it turn out badly. You haven’t gotten any better as an actor and you feel bad, too.”

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Gallagher appeared on television in a range of movies and shows, but never anything as popular as The OC. He says he liked the script from the outset: it was written well and he wanted to play a “real dad.”

“Oftentimes on TV it seems that men, especially fathers, are portrayed as hopeless boobs or impossibly impenetrable and enigmatic,” he says. “I don’t know too many guys like that. The fathers I know are often out there doing the best they can to fulfill their responsibilities as a parent and at work and never quite sure if they’re succeeding, but continuing to try anyway.”

Feeling Real

Like most actors, Gallagher can talk about career ups and downs. He remembers struggling with a crisis of confidence at age 29. “I didn’t feel real enough,” Gallagher recalls. “You can either keep doing the things you’ve been doing and banging your head against the wall, or you reassess things and do what needs to be done. For me, I just wanted to start over.”

He found that new beginning when he began to study privately with the Russian acting teacher Mira Rostova. Twenty years later they continue their professional relationship. “I think she’s a genius,” he says.

If being a lifelong student of acting keeps him grounded in the craft, his family keeps him grounded in what really matters. “Having a life is wonderful,” he says. “It’s really what informs the work. I don’t know how effective I could be as an actor if I didn’t have some notion of what it means to be a parent and a husband. And this life you build from scratch, it’s the real thing.”

It’s also precious. The first year of The OC, Gallagher commuted between California and his New York home, but it was too hard on the family. Gallagher missed the kids’ ice hockey games, dance concerts, and family meals. Once it became clear that The OC had staying power, his family moved to join him in California.

“When you have a child, you really learn about love,” he says. “You realize your well-being is tied up with this other’s for the rest of your life. And it’s terrifying. And it’s real. If my kids reach adulthood intact, and I die before they do, then anything else is gravy.”

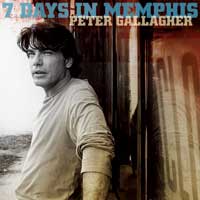

One unexpected bonus of The OC is a return to singing. Sony, looking to attract an older female audience, contacted Gallagher after hearing him sing in an episode. The CD, titled 7 Days in Memphis, features songs by Isaac Hayes and David Porter, Randy Newman, and Lucinda Williams, among others. “When he sings around the house and I hear him,” Harwood says, “I think it’s so gorgeous. That’s when I think, I hope others would hear this, too.”

“I started out as a singer,” Gallagher says. “And in my heart of hearts, I’ve always felt that’s where I’m most effective.”

He recalls the recording session: “I’d be in the booth singing and just saying to myself” —his voice drops to a low whisper— “Remember this. This is one of the best moments in your life.”

It’s that perspective that probably sets Gallagher apart from actors seduced and often disappointed by the glint and glimmer of Hollywood. He counts himself fortunate to have simply endured in the fickle, highly seasonal entertainment business. He knows from experience that as quickly as acclaim arrives, it can disappear.

“I had so few expectations about—and had such a bleak outlook for—what life in the theater might offer, that the longer the journey continues, the more extraordinary the whole thing is,” he says. “Anthony Hopkins says you can’t get extraordinarily successful until you are the age you feel inside. I never felt like a young kid. I’m just coming into my own.” |