| |

Sports

Go Jumbos!

A History of Tufts Athletics

By Mark Herlihy, A88, with contributing reporting by Paul Sweeney

|

The 1870 baseball team participated in the first intercollegiate

athletic contest when they played a game against Brown in

1869.

|

Sidebar:

Raising

the Bar: Rudy Fobert A50, G51

Sidebar:

Just

Vera: Vera Stenhouse, A91

As Tufts celebrates 150 years, one thing is clear: athletics have

been and remain an integral, defining part of the Tufts experience

for the thousands of students, alumni, faculty and staff who have

taken pride in their accomplishments. After a modest start, athletics

at Tufts grew steadily over the years, weathering, like the University

itself, world wars, economic downturns and periods of intense civil

discord. Programs came and went, but over time, athletic opportunities

for undergraduates expanded. Today, nearly 800 Tufts students participate

in sports each year. For these student-athletes, and for their predecessors

on the Hill, athletics have complemented academics and taught valuable

lessons about the importance of preparation, teamwork, poise, discipline,

and the ability to win and lose with dignity.

In an age in which the line between big-time college athletics

and professional sports has blurred, and scandal taints the reputations

of many prominent programs, Tufts athletics have remained relatively

pure through a steadfast commitment to the amateur ideal. As a Division

III school, and charter member of the New England Small College

Athletic Conference, Tufts has accorded sports an important but

not necessarily privileged place in the life of the University.

While Jumbos have sought glory on athletic fields of battle, the

University has refused to lower academic standards to fill rosters

with blue-chip players. As former president Nils Y. Wessell wrote

in his memoir, "In all its intercollegiate athletic history,

Tufts followed a policy of amateurism. Participants were drawn from

a student body which included no members seduced by athletic scholarships."

"The history of athletics at Tufts is student-initiated, student-centered

and community-oriented," said Rocky Carzo, athletic director

at Tufts from 1974 to 1999 and currently coordinator of "Jumbo

Footprints," which traces the history of Tufts Athletics. "The

purity of sport in our particular program is that it's voluntary.

There's no requirement. You choose to do it and the reason you choose

to is because it's fun. There's fun in moving your body, running,

training and seeking the reward that comes with it."

Yet despite an emphasis on participation and the amateur ideal,

the history of Tufts athletics is marked by many impressive individual

and team accomplishments. The history of Tufts athletics is almost

as long as the history of the University itself.

Intramural and club baseball and rowing teams made a home at Tufts

soon after the college was founded. The first intercollegiate athletic

contest in which a Tufts team participated, a baseball game against

Brown, occurred in 1869. Prior to that time, groups of Tufts students

participated against each other on an intramural level and against

local town teams. Evidence suggests that Tufts students in the mid-1860s

played football under rules that made the game resemble what we

today call soccer. In 1874, informal track and fencing teams were

organized. Two years later, students formed a rifle club that competed

against other college teams.

Easier to document is the contest that took place on June 4, 1875,

when a group of Tufts students played Harvard in what several historians

consider to be the country's first college football game played

under American football rules-featuring catching and running with

the ball. Tufts, coached by student captain Lyman Aldrich, A1876,

won this historic event 1-0. Another member of this inaugural event

was Austin B. Fletcher, A1876, for whom the University's School

of Law and Diplomacy is named. Eugene Bowen, A1876, served as the

manager of the first Tufts team, and he later detailed the event

in a letter to Tufts football coach Fred "Fish" Ellis

in 1949.

"For the game at Harvard, the students 'borrowed' horses and

the hay wagon, the students climbing on the wagon, driving down

North [Massachusetts] Avenue, with a growing number of urchins and

others at leisure calling us farmers and hayseeds, jeering our progress

toward Cambridge to play mighty Harvard," Bowen wrote.

During Tufts' first 30 years, sports teams were student-run, fledgling

enterprises, and interest varied from year to year. Baseball enthusiasts

had to cajole classmates to play in order to field a team. Students

financed their own uniforms, equipment and transportation to away

games. There were no paid coaches. In this era the University did

not sanction or support athletics financially. Indeed, many administrators

and faculty members believed athletic competition and intellectual

contemplation were incompatible, that good athletes could not be

good students.

In time, sports became more accepted and institutionalized at Tufts.

Recognizing the increasing importance of sports to the overall undergraduate

experience, the University in 1894 constructed an outdoor sports

complex on the lower campus which included the Tufts Oval (present

site of the outdoor track), a football field and a baseball diamond.

In 1899, Tufts President Elmer C. Capen endorsed athletics by speaking

publicly of his "conviction that good wholesome athletics had

a large place to fill in the education of the future." While

supporting sports both financially and rhetorically, the University

also began to exercise greater control. Administrators in 1899 ruled

that participation in athletics would be a privilege to which only

students in good academic standing would be entitled, and that athletes

would henceforth not receive special treatment on campus. These

ideas have informed the philosophy of Tufts athletics to the present

day.

The turn of the century marked the first signs of the formalization

of athletics at Tufts. An athletic association manned by faculty

and students drafted a constitution to develop guidelines of participation

and administration for the young program. During the same time,

T. S. Knight, A1903, was the first Tufts football player named to

Walter Camp's All-America team. The son of a Tufts theology professor,

Knight later became a trustee at the University in 1927.

|

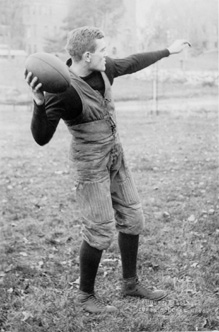

George Angell, A1915, a member of the 1913 football team,

was reputed to have thrown the first forward pass in football

history.

|

In the early decades of the 20th century, athletics continued to

evolve on the Hill. The beginning of a Jackson Athletic Association

for women was demonstrated by women competing in a freshman-sophomore

baseball game in the annual Jackson Field Day. The 1913 football

team, led by Clarence "Pop" Houston, A1914 (who would

later become the first athletic director), Bill Parks, D1916, Bill

Richardson Sr., A1915, H1940, Ollie Westcott, D1917, George Angell,

A1915, and Moze Hadley, E1915, was one of the most dominant in the

East, posting a record of 7-1 and outscoring its opponents 174 to

22 along the way. A team noted for its passing, uncommon at the

time, Angell was reputed to have thrown the first forward pass in

football history. The team's only loss came to Army by a score of

2-0 (the Cadets scored on a safety) in a game in which Army sophomore

halfback Dwight D. Eisenhower suffered a broken leg. Eisenhower

later wrote to Tufts president Wessell in 1955, declining an honorary

degree invitation due to his busy schedule, but also confirming

his injury at Tufts. "No wonder that my knee has never quite

recovered from that tackle," Eisenhower wrote. "At the

very least, I find some consolation in blaming all my poor golf

shots on my bad knee."

The 1920s saw the emergence of arguably the greatest athlete to

have ever worn the brown and blue. Fred "Fish" Ellis,

E29, quarterbacked the undefeated football team, coached by Arthur

Sampson, A21, in 1927 and earned All-New England honors in football,

basketball, baseball and track, the first Tufts student to do so.

While "Fish" was the big man on campus, his wife-to-be,

Dorie Loughlin, J31, was a member of the Jackson baseball team.

"I recall a game against Pembroke at Tufts at which several

of the football players wandered over after practice to give us

support," Dorie said. "As to the score of this game, my

memory does me no favors. However, I have one recollection of a

very sore, bone-bruised hand, even though I stuffed a bulky handkerchief

in my shortstop mitt to soften the impact of a line drive."

That same decade witnessed tremendous growth in Tufts athletics.

Thanks to a donation of lumber from an alumnus, the University was

able to build new stands at the Oval. "In a show of school

spirit, the construction of these stands was completed not by contractors

but rather via an inter-fraternity competition of sorts, with each

fraternity building a different part of the structure in order to

hasten its completion," writes Christina Szoke in an essay

on Tufts athletics. Golf, hockey, swimming and wrestling teams were

formed in this decade, dramatically increasing the number of sports

that men could pursue.

Opportunities for women increased as Jackson students for the first

time competed in tennis, golf, volleyball and horseback riding.

Despite the Great Depression and its effect on the country in the

1930s, new athletic programs and facilities were added at Tufts

during this decade. Lacrosse became a varsity sport in 1930. Bill

Hersey and Luther Child, both Class of 1932, will be recognized

this spring as members of the first lacrosse team at a Tufts game

versus Williams. Soccer gained formal recognition during the 1934-35

academic year.

The most notable development in athletics in that time was the

construction of Cousens Gymnasium in 1931. President John Cousens,

A1898, a former football player at Tufts, built the gym during the

Depression, an indication of the importance he placed on athletic

facilities and adding life to the campus. Upon completion, it was

recognized as the best indoor facility in the greater Boston area.

Until World War II interrupted life on campus, the 1940s promised

to be a memorable decade in the annals of Tufts sports. In 1940,

Edward "Eddie" Dugger, E41, turned in one of the most

impressive performances by a Jumbo ever when he won the NCAA 120-yard

high-hurdles championship. Dugger's time of 13.9 seconds established

a new NCAA and U.S. record in the event, one that stood for five

years. As the country mobilized for war, however, interest in athletics

waned. While Tufts fielded teams in the war years, sports, like

many aspects of American life, lost some luster. The 1942 Jumbo

Book captured the transformation when it asserted that, "The

world conflict in which our nation is involved at this eventful

time has changed the character of Tufts. For, while depicted here

is a normal year at Tufts-a pleasant place to work and play-war

and worse, an end to democracy, may end such years for centuries

to come." Many student-athletes adapted to war-induced changes.

"The Jackson Athletic Association arranged a field hockey

game with some sailors from the British Royal Navy," said Harriet

Gaffny Palmieri, J45. "To our astonishment, it was an all-male

team. Our team, captained by Maxine Lybeck, J45, made a valiant

effort, but the Englishmen won, 3-1."

After years of privation, Tufts students in the postwar era (more

than 3,000 students, mostly from the armed forces, the largest student

body to date), indulged in athletics with renewed vigor and enjoyed

some spectacular successes. The 1950 baseball team, after compiling

a 16-4 record, played in the College World Series in Omaha, Nebraska.

The 1949-50 basketball team, led by Jim Mullaney, A51, Al Perry,

A50, and Don Goodwin, A51, posted a 19-4 record-the best ever for

a Tufts hoop squad- and was considered to be the best team in the

area. Cross-country runner Ted Vogel, A49, placed third in the Boston

Marathon in 1947 and represented the United States in the 1948 Olympics.

The, men's track team, featuring Charlie Kirkiles, A49, Alan Wolozin,

A48, Charlie Johnson, A49, Eddie Palmieri, A46, Bob Backus A51,

and Tom Bane, A51, enjoyed undefeated seasons in 1948 and 1949.

Backus went on to compete in the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, where

he placed 13th in the 16-pound hammer throw. Of all the talented

athletes at Tufts in this era, none was more versatile than Rudolph

J. Fobert, A50, G51. Fobert earned 12 varsity letters, four each

in football, baseball and track.

Despite the impressive achievements of athletes and teams in the

postwar era, an innocence and purity still pervaded the Tufts sports

world.

In the 1960s, several teams had particularly strong campaigns and

several individuals predominated. During the 1966-67 academic year,

both the cross-country and indoor track teams, led by Bruce Baldwin,

E68, Ron Caseley, E68, and Chris Kutteruf, A68, went undefeated,

while the outdoor squad lost only one meet. The 1967 men's soccer

team enjoyed one of its best seasons ever. Led by co-captains Dick

Dietrich, A68, and Roger Mattlage, A68, Tufts won the New England

College Division Championships and the Greater Boston Championships.

Rich Giachetti, A70, was football's national leader two consecutive

seasons in pass receptions. Pitcher Bill Richardson, Jr., A70, helped

lead the Tufts baseball team to the Greater Boston League Championship

in 1968. Richardson would later serve as a U.S. congressman, U.N.

Ambassador and Secretary of Energy under President Clinton. Swimmer

Craig Dougherty, A79, earned All-America honors in his junior and

senior years, and established records in the 50 and 100 meters that

still stand.

"[Men's Swimming Coach] Don Megerle would take a personal

interest not only in our athletic contributions, but also in our

personal lives," Dougherty said. "He had a way of raising

the bar incrementally that allowed athletes like me to tolerate

exhaustion and pain at a level we never thought possible. It was

a process that taught us how to break through a barrier, knowing

that you could continue to keep improving, to keep pushing the body

and the mind to incredibly high thresholds. I do the same in the

real world of business. It works."

Athletic opportunities for women increased dramatically after passage

of Title IX in 1970, and women athletes at Tufts distinguished themselves

through individual and team accomplishments. Maren Seidler, J73,

competed in the javelin at the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Women's

sports at Tufts truly emerged in the 1980s. Cecelia Wilcox Paglia,

J87, scored 156 goals for a powerhouse lacrosse team in the mid-1980s

that lost only four games in as many years. The women's tennis team,

which included twins Lisa and Nancy Stern, J86, captured four consecutive

New England Division III titles between 1983 and 1986. Vera Stenhouse,

J91, was an eight-time national champion and 23-time All-American

in track and field.

Male athletes also continued to excel. In track and field, Fred

Hintlian, A76, was a Division III national champion and three-time

All-American in the 440-yard hurdles. Eric Poullain, E84, M84, came

to Tufts from France and earned Division III All-America honors

numerous times and was national champion in the pole vault. Mark

Buben, A79, set single-season and career records for sacks in football

and played for the New England Patriots for several years after

his collegiate career.

The 1979 football team, quarterbacked by All-American Chris Connors,

A80, posted the third and most recent undefeated season at Tufts.

In 1986, baseball pitcher Jeff Bloom, A88, attracted national media

attention by throwing three consecutive no-hitters.

Perhaps the most impressive development in Tufts athletics in the

recent past has been the emergence of the sailing team as a national

dynasty. Tufts' teams, which hone their skills and host regattas

on the Upper Mystic Lake in Medford, have captured 22 national collegiate

championships since 1976, while numerous former Tufts sailors, men

and women, have gone on to win world championships. The team's "Hall

of Fame" includes greats such as Betsy Gelenitis, J81, Dave

Curtis, A69, Manton Scott, A74, Peter Commette A77, Magnus Gravare,

A86, and others. Current Tufts president Lawrence J. Bacow raced

against these individuals as a skipper for MIT.

While Tufts student-athletes have distinguished themselves individually

and collectively during the last quarter century, the University,

often with generous support from alumni, has kept pace with facilities.

The Baronian Field House, raised by the generosity of many alumni

and named for former Jumbo football player John Baronian, A50, was

added to the Ellis Oval complex in 1986. Soon after, the football

field was redone and named in honor of former player Harold Zimman,

A38. The cinder track was replaced with an eight-lane synthetic

surface in 1989 and named after legendary Tufts and Olympic track

coach Clarence "Ding" Dussault. A press box was constructed

and named in honor of Arthur Harrison, A42, by his family in 1991.

In 1993, a comprehensive fitness center was built through the extended

generosity of Steve Ames, the Peter Lunder Family, the Zimman Family,

John "Jocko" Lee, A50, and John Bello, A68. The same year

donations from former football captains, led by Bob Bass, A70, were

critical towards building the Captain's Gate at the entrance to

the Ellis Oval. The Cheryl Chase Family gave the lead gift for the

construction of an intramural gym in 1995. Tufts Chairman of the

Board of Trustees Nate Gantcher's family made the largest single

donation to the athletic department for a state-of-the-art sports

and convocation center, which opened in 1999.

Alumni interest in Tufts athletics is best represented by two leadership

groups. The Tufts Jumbo Club, established in 1969, and the Board

of Athletic Overseers, gathered in 1989, showed a loyalty and advocacy

to Tufts athletics that was previously undemonstrated. The Jumbo

Club initiated numerous gifts, equipment, facility renovations,

and awards that weren't possible without their funding. The Board

of Overseers, under the astute leadership of John T. O'Neill, A50,

not only advocated, but planned and fund-raised for the greatest

facility expansion since the 1930s. As a result, the Tufts Athletic

Department now has facilities to accommodate the University community

and compare with peer institutions. "The advocacy and support

that they offered the athletic department enabled us to enter the

21st century with a great deal of confidence," Carzo said.

Tufts athletics continued to make history in the 1990s and into

the new millennium. Along with the new facilities, the University's

athletic teams, athletes, staff and alumni gained frequent recognition

on a national level. Johnny Grinnell, A35, an All-American on the

1934 undefeated football team, was inducted into the College Football

Hall of Fame in 1997. In January 1999, the NCAA bestowed the Teddy

Roosevelt Award, its most prestigious honor, upon Richardson for

his national achievements as a former varsity athlete. Richardson

shares the award with four former Presidents of the United States

(Eisenhower, Ford, Reagan and Bush). As members of the strict New

England Small College Athletic Conference, Jumbo teams were finally

permitted to play in NCAA Tournaments beginning in 1993. Several

teams qualified, with women's soccer hosting the 2000 "final

four" in Medford and advancing to the national championship

game. Men's cross-country and softball are the teams that have enjoyed

the most NCAA Tournament success during the decade.

Beyond competitive success, for many Tufts students, athletics

enhance and help define the undergraduate experience.

"If it was not for the track team, I don't think I would be

the person that I am today," said Kara Fothergill, J95. "All

of the coaches at Tufts do their best to make the athlete's experience

the best it can be whether you are male or female. Every school

has its quirks, but I think Tufts works hard at providing equal

opportunities for men and women."

The same spirit that was demonstrated by students riding a hay

wagon down Massachusetts Avenue for a football game at Harvard in

1875 also inspired astronaut Rick Hauck, A62, to carry the Tufts

flag on a space mission on the shuttle Challenger in 1983.

The spirit remains today, evident when 2,000 students marched down

to Kraft Soccer Field for the NCAA women's championship game in

2000.

Go Jumbos!

top

Raising the Bar: Rudy Fobert A50, G51

A discussion about who is the finest male athlete in Tufts history

should center around Fred "Fish" Ellis, A29, and Rudy

Fobert, A50, G51. Both excelled in four sports during their Tufts

careers, but Ellis himself, who coached Fobert in football, once

said that Rudy was more deserving of the title.

Fobert was a forefather to the Tufts philosophy of encouraging

athletes to play more than one sport. He played two sports in a

day. During the spring he was an outfielder for Jit Ricker's baseball

teams, then he would run up to the Oval to jump and sprint for Clarence

"Ding" Dussault's track teams. A recipient of 12 varsity

letters in three years (freshmen weren't eligible), he also competed

for the football and indoor track teams. He was a member of the

1950 baseball team that advanced to play in the prestigious College

World Series in Omaha, Nebraska.

Fobert was raised in East Boston during the Depression, one of

eight children living in a three-decker. These humble beginnings

were reflected in the man's personality. He was soft-spoken and

modest, but clearly focused on making something of himself. His

determination towards academics was equal to his athletic preparation.

"Rudy was a solid physical specimen," said John Baronian,

a football teammate and friend of Fobert's. "He was only 5'8",

175 pounds, but no one had a better physique. He was the best coordinated

athlete I ever saw."

Like Ellis, Fobert went into education professionally. He served

as superintendent of the Lexington, Massachusetts, school system

and was president of the Massachusetts School Superintendents Association.

He remained dedicated to his alma mater, serving five years as a

trustee of Tufts and as chairman of the Tufts Alumni Council.

Tragically, Fobert died young, at 51, due to cancer, in 1978. The

Rudolph J. Fobert Award was established in his memory and is presented

every year to the male and female multisport athletes with good

academic averages and potential for leadership.

-Paul Sweeney

top

Just Vera: Vera Stenhouse, A91

When Tufts track coach Branwen Smith-King first met Vera Stenhouse

in 1988, she could hardly contain her excitement. The coach could

see right away that this elegant, six-foot athlete would be something

special with some training.

As anticipated, Stenhouse evolved into the most decorated female

athlete in Tufts history. She won eight NCAA national championships

while competing indoors and outdoors: four in the triple jump, three

in the 400 meters and one in the 200 meters. As a senior in 1991

she won four national titles and single-handedly led Tufts to fourth-place

finishes at both the NCAA indoor and outdoor championship meets.

Twenty-three times she recorded All-America efforts at the track

nationals.

"Vera was not just gifted, she was very intuitive as far as

knowing what she had to do," Smith-King said. "She did

a lot of searching, always driving for more knowledge on how she

could improve."

Stenhouse's ability was so superior to her teammates that Smith-King

was challenged to come up with alternate ways to train her superstar.

Despite this gap in talent, she was just one of the girls off the

track. She had the potential to compete at the Division I level,

but instead chose a more familial opportunity at Tufts. The magnitude

of her accomplishments put her on a national stage, but she was

unassuming all along.

"Vera was just Vera," Smith-King said. "She came

from a wonderful family and it showed."

She was much more than a graceful runner and jumper at Tufts. An

English and astronomy major, Stenhouse earned an NCAA postgraduate

scholarship for her achievements athletically and academically in

1991. The Tufts Alumni Association also presented her with its Senior

Award for outstanding academic and community accomplishments.

One of a few Tufts athletes who continued to compete after graduation,

Stenhouse competed at the United States Track and Field National

Championships a few years ago, rubbing shoulders with track legends

such as Jackie Joyner-Kersee.

-Paul Sweeney

top

|