|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

FEATURE

|

|

|

| |

Movie

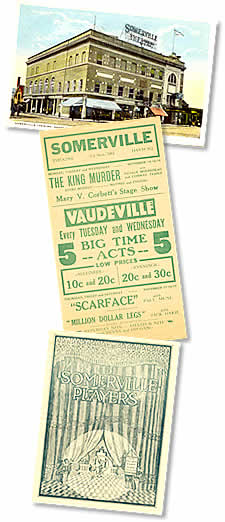

ephmera courtesy of David Guss

|

Lost Palaces

Remembering the Movie Houses of Somerville

by Coco McCabe

Red fabric printed with gold covers the

walls of the balcony at the Somerville Theatre, where chandeliers

hang at a dizzying height. A ceiling mural dances in a medallion

high above the movie screen. Intimacy and anticipation fill

the darkness below. Not much has changed here since 1914 when

the theater opened. The sense of escape is as powerful as ever.

“When you walk in there alone, you feel the magic,”

said David Guss, associate professor of anthropology at Tufts.

It was that magic Guss and his students went in search of last

year, and are continuing this spring. Their mission: to track

down and tell the stories of the 14 neighborhood theaters that

once dotted the city. There was the Capitol and Pearson’s

Perfect Pictures and the Teele Square, the Orpheum and the Strand.

For a mere 10 cents, Somerville’s theaters offered patrons

ample fare: newsreels, Westerns and Hollywood glamour in movies

featuring such stars as Shirley Temple, Clark Gable and Katharine

Hepburn.

Today, only the Somerville Theatre in Davis Square remains.

Parking lots and storefronts stand where the theaters once drew

crowds. But through oral history and collecting paintings and

photographs, playbills and lobby cards, Guss and his students

in Anthropology 185A have created an exhibition that reveals

the vibrant role of Somerville’s neighborhood theaters

as cultural, social and economic anchors.

Called “Lost Theatres of Somerville,” the exhibition

opened at the Somerville Museum in March, and features both

student work and the vast collection of Guss’ own theater

paraphernalia. “We have created a collection of the movie-going

experience, which almost nobody in the country has,” said

Guss. “People in the community want this to happen. These

were places really important to them. This is the history of

their childhood and their past.”

That history—alive, but hidden to many eyes—was

the perfect medium for training anthropology students in some

of the technical skills of their field. It’s the history

of a vibrant world, with its own architectural legacy, and it

happens to be right outside their dormitory doors.

Guss’ seminar, “Theatres of Community and the Social

Production of Space,” focused on the role movie theaters

played in defining neighborhoods and in offering people common

emotional experiences in the age before suburbia and TV so dramatically

altered the physical and psychological landscape.

Teamed with student partners from Somerville High School, Tufts

students fanned out through city neighborhoods to record the

oral histories of former theater personnel and patrons. Such

histories are one of the strategies used in ethnography—a

cultural study that allows an anthropologist both to observe

and interact with people in their environment.

For senior Emily Pingel, the experience changed her whole relationship

with the city. “It was my first brush with doing ethnography

and finding right from the source the answers you’re looking

for,” she said. “I had never conducted an interview.

I had no idea where my boundaries were.”

It didn’t take long to find out. Strangers willingly opened

their doors, and their hearts. “It made a big mark in

my college career,” she added. “I now feel like

I’m more part of Somerville rather than being a transient

person here for college.”

For his final project, Stephan Lukac, A02, made a documentary

video based on the interviews he conducted with 12 people. The

piece will be included in the exhibit.

“What attracted me was a real-world chance to do an ethnography,”

said Lukac. “That’s what anthropology is. It’s

going to a group and immersing yourself in it.” He won’t

soon forget the lessons he learned.

“A lot of people opened my eyes about the Depression and

how it impacted their lives,” said Lukac. “They

got by with nothing.”

But they had the movies.

“It was a night to go out,” recalled Jennie Vartabedian,

a 91-year-old Somerville resident who at various times ran a

candy shop, an ice-cream parlor, and a sandwich shop that all

catered to the moviegoing crowd. “You sat and relaxed.

You looked forward to it.”

For patrons who needed a little nudging, there was “dish

night” when theaters would offer women a free piece of

china if they came to the movies. If they came often enough,

they could collect a whole set.

Evelyn Battinelli’s mother did. The assistant director

of the Somerville Museum, she still has her mother’s set,

and the memories it sparks are poignant.

“You think back to what life was like at that time,”

she said. “Years ago everybody would buy a little of this,

a little of that. Everything was mismatched. That’s why

there was this draw to collect china.”

Theaters offered other treasures as come-ons. “One night

they gave away a fur coat,” said Val Viano, 84, whose

late husband and brother-in-law were former owners of the Somerville

Theatre as well as the theaters in Teele Square, Broadway, and,

in neighboring Arlington, the Regent and Capitol theaters.

She still goes to the movies, but it’s not the same. The

cineplex, a string of shoebox theaters connected by a long hall,

will never measure up to the handsome auditoriums of an earlier

day. “I don’t think it’s the fun experience

it used to be,” she said.

With the help of persuasive proposals, Guss was able to take

those memories, combine them with his own private collection

of movie theater materials, and prepare them for a wider public

appreciation.

Besides a $5,000 seed grant from former provost Sol Gittleman,

other sources of funding include $10,000 from the University

College of Citizenship and Public Service, $15,000 from the

Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities, and $900 from the

Somerville Arts Council. The Somerville Theatre has also pledged

$5,000. A $4,300 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities

will fund an assessment of storage facilities at the Somerville

Museum as part of the first step toward a permanent archive

for the fragile movie-theater materials.

In addition, a $12,000 grant from the LEF Foundation has allowed

Guss to commission six photographers to document what’s

left of Somerville’s theaters. Tufts graduate Stefanie

Klavens and Jim Dow, a faculty member in the school’s

Visual and Critical Studies Department since 1973, are two of

six photographers chosen for their variety of artistic interpretation

and style.

Among the pictures Somerville photographer Henry Cataldo has

shot are some of the Odd Fellows Hall that once housed Pearson’s

Picture Perfect. Cataldo happened to catch the building as fire

tore through it in 1975. He watched over the years as it became

an empty lot and now a medical center, which he photographed

during its final phase of construction. “I like observing

things over the passage of time,” said Cataldo.

Adds Klavens, who photographed the Broadway Theatre just prior

to its being converted into pottery studios, “It’s

bittersweet to see what remains. I don’t think of these

theaters as ‘old-fashioned’ but as something deeper.

They were a place to dream.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|