Cabinet of wonders

research by Rasika Welankiwar

photographs by Jeffrey Coolidge

A few weeks ago, we sent curators, librarians, and archivists at Tufts on a vital mission. We asked them to scour their collections for items that might fill a "cabinet of wonders," one of those old-time display cases devoted to two-headed frogs, glass eyes, fragments of Egyptian pyramids, and other curiosities. Inasmuch as ours was to be a "virtual" cabinet—it would exist only in these pages—the sky was the limit. Specimens could be big or small, ancient or modern, imposing or humble. There was just one condition: each item had to be very cool—so cool it would impress a 10-year-old.

Our experts brought forth a wondrous assortment of artifacts. They showed us cuneiform tablets, grisly anatomical drawings, foxed pamphlets from Colonial times, even blueprints from a proposed Big Dig of the 1940s. Each object was, in its own way, cool. What we present here, in our cabinet of wonders, is the coolest of the cool, the items that made our inner 10-year-old go oooooh.

|

| University archives. Gift of the Dolbear family |

Singular wireless

Among the many competing designs for a speaking telephone in the 1870s was a wireless model invented by Amos Dolbear, then head of Tufts' Department of Astronomy and Physics. The first transmissions with the "induction wireless telephone" took place between Dolbear's laboratory in Ballou Hall and his home on Professor's Row. Although the device was less practical than the one patented in 1876 by an upstart named Bell—its magnetically induced signal could travel barely a mile, and apparently was unrecognizable as speech—it offered a distinct advantage over today's wireless phones: to place a call, you first had to jam a metal rod into the ground. In other words, no gabbing in restaurants or on the road.

|

| Hirsh Health Sciences Library special collections |

Blood simple

Until the 20th century, blood transfusions were an intimate affair. Donor and patient had to be present at the same time, the blood transferred through syringes or tubes, or even by suturing the donor's artery to the recipient's vein. Then, in 1915, Richard Lewisohn, at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, found a way to keep donors' blood from clotting. His transfusion method added sodium citrate, an anticoagulant, to the blood, allowing it to be stored for several days. A few refinements later—including the introduction of refrigeration and stronger anticoagulants—the modern blood banking system was born.

|

Murrow Memorial Reading Room, Edward R. Murrow Center for Public Diplomacy.

Gift of the Murrow family |

Edward R. Murrow: The Hat

As German bombs rain down upon the British capital, a lone figure stands atop BBC Broadcasting House, cocks his trusty cap, and intones into a radio mike, "This . . . is London." Actually, we don't know when the famous newscaster wore his U.S. War Correspondent garrison cap, but it's among the personal effects to be found in Tufts' Edward R. Murrow Collection, along with Murrow's papers and library.

Tail of the Great One

Tufts affiliates will hail the mortal remains of the university's mascot. All others will reverently attend the story: In 1889, P. T. Barnum donated to Tufts the stuffed hide of Jumbo, the largest elephant ever seen in  America and former star of "the greatest show on earth." Before taxidermy, Jumbo weighed in at 6 1/2 tons and stood almost 12 feet tall. Students would yank on Jumbo's tail and place a coin in the curl of his trunk for luck. All the tugging took its toll, and eventually Jumbo's tail pulled right off. The rest of Jumbo was destroyed in a fire in 1975, but his tail stayed safely tucked away in University Archives. America and former star of "the greatest show on earth." Before taxidermy, Jumbo weighed in at 6 1/2 tons and stood almost 12 feet tall. Students would yank on Jumbo's tail and place a coin in the curl of his trunk for luck. All the tugging took its toll, and eventually Jumbo's tail pulled right off. The rest of Jumbo was destroyed in a fire in 1975, but his tail stayed safely tucked away in University Archives.

|

| Dr. H. Martin Deranian Dental Museum, Tufts School of Dental Medicine Collections |

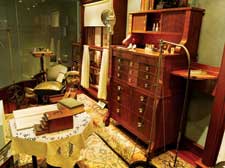

Dental flashback

Now here's a piece of Americana you didn't know you wanted to preserve: a fully equipped dental office, vintage 1899. The core of the exhibit is courtesy of H. Martin Deranian, D.D.S., who taught dental history at the School of Dental Medicine for 40 years. The latest technology—a foot-powered drill that could reach 1,000 rpm (about 1,000th the speed of today's dental drills)—here coexists with Grand Guignol torments like the tooth-extracting key, about which Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, "There never was a claw on a bird or beast that was the cause of such anguish or apprehension, such howls of agony."

|

| "Seated Figure: Shell Skirt," Permanent Collection of Art. Gift of Jeffrey Loria, A90P |

Pocket-sized Henry Moore

Yes, that Henry Moore. He of the sprawling outdoor sculptures so massive that art thieves, like the ones who lifted a $5 million reclining nude in Great Britain last December, can't do the job without a crane and a flatbed truck. Tufts' Henry Moore, a bronze maquette, or model, for a sculpture that was never cast, is just six inches high.

|

| Permanent Collection of Art |

Ivory league

Elephants. Three thousand of them. All donated by one Jumbo devotee, John Baronian, A50, H97 (known on campus as "Mr. Tufts"), who collected them in 50 years of world travel. We've got bronze elephants, silver elephants, wooden, plastic, and ceramic elephants. Elephants from Hong Kong, Thailand, Africa, and Europe. Marching elephants, charging elephants, even a violin-playing elephant. And this one, which caught our eye just because it's cute.

|

| Tisch Library special collections. Gift of Walter F. Welch, A28 |

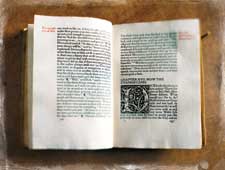

Xtreme self-publishing

William Morris, the Victorian artist, writer, and socialist rabble-rouser, gave new meaning to the phrase "do-it-yourself book." In the 1890s, he founded his own publishing house, the Kelmscott Press, to produce limited editions of Chaucer, the classics, and modern works. Then he designed his own typefaces (Golden, Chaucer, and Troy), commissioned special handmade paper ("wholly of linen," "laid and not wove"), designed the decorative borders and illuminations—like the lush capital shown here—and hand printed every volume, including this 1893 edition of News from Nowhere, a "utopian romance." Oh, yes, he also wrote the book.

|

| Hirsh Health Sciences Library special collections. Gift of Murray L. Shipp, M39 |

Cold steel

You'll want to squint through your fingers at this Civil War surgical kit, in which everything is pretty much what it appears to be. The large, flat instrument is (you guessed it) a bone saw, the long knives are for amputations, the cloth belt is a tourniquet, and the three vertically arranged tools are trephines, for drilling the skull. Mercifully absent is a bullet for biting; contrary to Hollywood, nearly all Civil War surgeries were done under a general anesthetic—chloroform or ether.

|

| University Archives |

Holy rollers

We love the weird juxtaposition of themes in this children's "Peace Puzzle" from 1915. The object was to "roll America's cannon balls"—the now mangy plastic spheres—"onto the cross." We think it's a swords-into-plowshares kind of thing (this being two years before the United States entered World War I), but the inscription on the lid makes us wonder: "It is not the amount of money you take out of this world, but the amount of love you put into it, that counts with God." All this in a package that resembles a snuff tin.

|