Hands

Across the Mystic

Protecting a vital watershed brings Tufts

and community advocates together

by Laura Ferguson

Photos by Richard

Howard

|

|

| |

| |

|

Michele Cutrofello strides into the Mystic

River with confidence. As an engineering student studying pollution

patterns in the Mystic watershed, she’s used to standing

waist-deep in water. It’s tricky today, though, as the

water level, higher than normal after recent heavy rains, nearly

crests at the top of her hip waders.

But on this bright October afternoon, Cutrofello is focused

on her science, not comfort. She’s inspecting the condition

of sensors at one of five Tufts’ river-monitoring sites,

most just five minutes’ drive from the Medford/

Somerville campus. The devices are keeping tabs on the levels

of oxygen in the water, its temperature, depth and other parameters.

As traffic swooshes by on busy Route 60, Associate Professor

of Civil and Environmental Engineering John Durant explains.

The project, known as EMPACT—Environmental Monitoring

for Public Access and Community Tracking—provides “real

time” monitoring of water quality; the sensors feed data

every 15 minutes into data loggers sealed in boxes on shore.

The loggers transmit the information back to Tufts, where it

is captured and fed into a website. Solar-powered panels keep

the batteries charged and ensure that the project runs around

the clock. Ultimately, this relay run supports an important

predictive tool. Watershed managers and the public soon will

be able to forecast the suitability of the river for recreational

use: swimming, fishing or boating.

“It’s a great project,” says Durant. “The

availability of timely information on water quality is important

because people may unknowingly expose themselves to potentially

harmful levels of waterborne pollutants. It gives us an opportunity

to make data immediately available to the public and ensure

that recreation is healthy for everyone.”

EMPACT is compelling simply by what it suggests: that the Mystic

River, a river characterized by both beauty and industry, could

become a popular urban recreational mecca. But that ambitious

vision is typical of a pioneering university and community partnership,

the Mystic Watershed Collaborative (MWC), drawing on the strengths

of Tufts University and the Mystic River Watershed Association

(MyRWA).

By working together, the collaborative promises to dramatically

increase the chances for watershed improvement at the same time

it enriches learning experiences for students and research opportunities

for faculty and graduate students. Faculty have won more than

$1 million in federal funding for basic science and engineering

research projects in the Mystic watershed, scrutinizing complex

pollution issues. Collaboration priorities have impacted the

Tufts’ curriculum, with faculty offering watershed projects

that encompass habitat restoration, public access and environmental

justice. And Tufts’ resolve to integrate watershed issues

with volunteer opportunities is instilling in students a sense

of civic duty.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Paul Kirshen, a research professor in Civil

and Environmental Engineering, and a driving force in the

collaborative, says that the collaborative’s success

comes down to a basic truism: there’s strength in numbers.

Tufts can reinforce local watershed leadership by contributing

academic resources and critically needed research. But the

partnership also brings new awareness to the fact that Tufts’

Somerville/Medford campus lies entirely within the Mystic

River watershed, something already appreciated by the Tufts

sailing team, which practices on Upper Mystic Lake, and by

the Tufts crew team, which recently moved from the Charles

River to the Malden River.

“One of the appeals of Tufts is that it is close to

the river,” said Kirshen. “But even though it’s

a marvelous resource worth protecting and making available

to everybody, not that many people know about it. So by collaborating

with a community organization we can help reawaken interest

in the Mystic as a place to recreate and enjoy nature. We

not only restore water quality but also restore the watershed

as a destination, as a place where people want to go.”

An Urgent Mission

Sun pours through the tall windows of the headquarters for

the Mystic River Watershed Association, where executive director

Grace Perez and two staff members run the day-to-day operations.

The small office, located in a renovated high school on a

side street in Arlington, Massachusetts, belies an umbrella

organization linking 225 members and more than 100 volunteers.

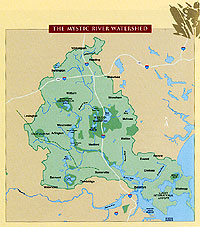

Upstairs, Perez talks about MyRWA’s territory: 76 square

miles encompassing 21 communities. The surface and groundwater

of the Mystic watershed flow downstream into the Mystic River

via its tributaries—Alewife Brook, Chelsea Creek, Mill

Brook, Sweetwater Brook, the Malden River and the Aberjona

River. This geography is seriously threatened by urban sprawl.

Roads, parking lots, rooftops and driveways that support half

a million residents also prohibit infiltration of rainwater,

and, instead, carry stormwater runoff directly into more than

40 lakes, ponds and wetland areas.

Perez points to a thin blue thread on a large wall map and

traces the course of the Mystic River as it winds toward the

Atlantic Ocean, where it merges with its more famous neighbor,

the Charles River, at the mouth of Boston Harbor. “We

can see that connections are being made across jurisdictional

lines by the water that’s carrying debris along with

it,” she says. “Contaminants from upstream are

working their way right past Tufts. You can’t ignore

the watershed perspective when you look at the river because

it’s affected by the land around it. I’ve seen

the worst pollution in the watershed in some of the weirdest

places, usually in the corners of towns, where no one really

wants to take responsibility. So from the perspective of the

watershed, where a town begins and ends makes no difference

to which way the water moves.”

MyRWA’s mission has perhaps never been more urgent.

The passage of the federal Clean Water Act in 1972 set a national

goal to eliminate all water pollution by 1985. But by the

30th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, the United States

is still far from its goal. According to the EPA, 45 percent

of surveyed lakes, 40 percent of rivers and streams, and 50

percent of estuaries are still polluted.

|

|

| |

| |

|

For MyRWA, pollution is one of the many

“top tier” priorities to restoring the watershed.

A key concern is what are commonly called CSOs, or “Combined

Sewer Overflows,” that discharge raw sewage directly

into waterways during heavy rainstorms. MyRWA is also very

interested in the cleanup of Superfund sites on the Aberjona

River. At the same time, access and proposed development projects

call for new ideas about land use. MyRWA, for instance, would

like to create a “Mystic Link” trail from the

Bay Circuit Trail in Andover through the Mystic Watershed

to Charlestown, but bridges and roadways block parts of the

proposed path.

In the meantime, MyRWA is taking an ambitious approach to

education. Hundreds turn out each spring for the “Herring

Run,” a 10-km foot race that celebrates the annual return

of migrating herring to the Mystic. From river cleanups, canoe

trips, walks and lectures, and a volunteer-based water-quality

monitoring program, the organization is enjoying a resurgence

of interest in protecting the watershed. “Our major

challenge is simply helping people understand what they can’t

see: that water that flows into storm drains, whether it is

in Woburn, Medford or Everett, ends up in Boston Harbor,”

says Perez. “So we can focus on what they can see: improved

access, safe fishing, swimming and boating. We need to show

that the Mystic can be a place to go for fun. The more people

we can bring down to the river, the more we can teach them

about the fantastic history and the flora and the fauna, the

more they will appreciate what they have.”

Coming Together

Paul Kirshen is one of many faculty who see what the Mystic

has to offer as he jogs along a curving, tree-lined route

from Tufts to the Upper Mystic Lake: other joggers, a kayaker,

the occasional motorboat puttering down to the homeowner’s

backyard dock, the dog walkers. “We’re people

who just enjoy the river for the river’s sake as well

as being interested in engineering and science,” he

said. “We’re always talking about the river, the

curriculum, graduate programs, research, and when we run we

do a lot of our best thinking.”

Kirshen founded and now directs the best example of that University-wide

preoccupation with water, the WaterSHED Center (see sidebar).

The universality of water and its critical role in sustaining

all life on Earth opens infinite possibilities for University-wide

teamwork. Still, Kirshen was looking to expand its reach when,

in the summer of 1999, he attended a workshop hosted by the

University College of Citizenship and Public Service (UCCPS).

Newly founded by former president John DiBiaggio, UCCPS invited

faculty to engage in discussions about integrating the values

of democracy and civic leadership into the curriculum. For

Kirshen, suddenly it clicked.

“I thought that the WaterSHED Center and Tufts as a

whole could focus a great project on the restoration of the

Mystic River,” he said. “It’s local. It’s

full of all sorts of interesting social, economic, scientific

and engineering problems. It seemed full of golden opportunities.”

The idea led to discussions with MyRWA, where Tufts already

had a strong link in John Durant, a MyRWA board member. “It

was a great opportunity for a partnership,” said Durant.

“The Watershed Association is understaffed and underfunded,

but they have all sorts of projects and Tufts has a lot of

expertise and resources, and we have students who are looking

for challenging opportunities.”

Others at Tufts shared that enthusiasm. In the fall of 1999,

University and community members gathered at a “Futures

Search” conference and emerged with major watershed

restoration themes. The venture later attracted almost 100

people to another meeting at Tufts. A steering committee of

Tufts faculty and students, MyRWA staff, the Massachusetts

Executive Office of Environmental Affairs and citizens took

shape, and by the spring of 2000 a veritable alphabet soup

of Tufts advocates had shown their support: UCCPS, Tufts Institute

of the Environment, the Department of Civil and Environmental

Engineering, and the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies

(CIS). Tufts representatives and members of the Mystic Watershed

Association devoted the next several months to planning, and

by spring, ideas had gelled around the new partnership called

the Mystic Watershed Collaborative.

“Most important about the Mystic Watershed Collaborative

was that it became a true university-community partnership

focused on achieving specific outcomes,” said Rob Hollister,

dean of UCCPS. “Across the United States, the vast majority

of university-based community service activities are driven

more by the interest of higher education than by community

priorities. And they lack sufficient outcomes orientation.

So I’m proud that the Mystic Collaborative has been

a real joint effort from the very beginning.”

The collaboration was officially announced at a press conference

in spring 2000, with President DiBiaggio and various state

and federal officials showing their support as well. The press

conference was held in Somerville on a Mystic River site known

as Blessing of the Bay, home to a Boys and Girls Club boathouse

and a few park benches. Here, Governor John Winthrop, on the

edge of his sprawling 600-acre farm, launched the Blessing

of the Bay, the first ship ever constructed on the river,

in 1631.

On this historic site, the collaborative made its own history

by officially pledging to make the Mystic swimmable and fishable

by 2010. “It’s fair to say that a deadline is

needed to get work done,” said Molly Anderson, director

of the Tufts Institute for the Environment (TIE) and the Tufts

liaison to MyRWA. “We’re actually playing catch-up.

Our sister river, the Charles, has gotten a tremendous amount

of state and federal support over the years and has always

had a higher visibility. We saw the Mystic as being urgently

in need of attention, and if we didn’t set a deadline,

efforts would likely drift along. We wanted to get it out

there and we wanted accountability from the parties that were

committed to change.”

Developing Ideas

The cause has been taken to heart. TIE jumped on board with

a conference, “Think Future, Act Now: Restore the Mystic

Watershed!” and a film festival. UCCPS has also provided

support. To diversify the collaborative’s financial

base, UCCPS initiated connections with funders and supported

a grant writer. These investments have helped the collaborative

to land a major federal grant and a significant private foundation

grant. UCCPS also steers several of its Omidyar Scholars to

the Mystic Watershed each year to learn from community partners

and design their own projects, mentored by MyRWA staff and

board members.

On the technology front, the Berger Family Technology Transfer

Endowment has funded the development of an interactive website,

the Mystic Watershed Collaborative Clearinghouse (www.tufts.edu/tie/mwc),

to consolidate and make accessible the wealth of information

available on the watershed as well as related watershed information.

The web-based resource makes available to the public reports,

data, historical maps and the capacity for creating new maps

with Geographic Information System (GIS) data.

And across the curriculum, the watershed issues have surfaced

among faculty with an eye toward incorporating local issues

into the classroom. Rusty Russell, an environmental law lecturer

in the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning,

for instance, “wanted to make law come alive by developing

legal questions in the form of team exercises. MyRWA and I

connected, and together we identified a set of issues that

were of top priority to the watershed.

“I felt pretty confident that students could have a

positive impact on real environmental problems if they worked

with the watershed association. Typically, those groups are

very aware of what the pressing environmental problems are,

but [they] lack the resources to move ahead. So it’s

a great synergy,” he said. In terms of efficiency of

time and effectiveness of teaching, “working in teams

and drawing on community resources is a great way to convey

key concepts,” he added. “And the watershed’s

chief concerns and challenges are awash with legal issues.”

One of the most successful curriculum-citizenship endeavors

to come from the MWC is the River Institute, now going into

its fourth year. The River Institute offers a seminar and

internships for students interested in a comprehensive approach

to addressing watershed issues.

Sociologist Dale Bryan, co-director of the Peace and Justice

Studies Program and experiential learning coordinator at the

Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, has nurtured the River

Institute from a seed of an idea to a program that appeals

to students both at Tufts and across the country. This past

year, the summer seminar was facilitated by an interdisciplinary

team of faculty. Some nine students were taught skills of

active citizenship while also learning about watershed community

issues through internships.

“As my colleague and co-director [John Durant] has said,

“I used to think that by using our extensive engineering

knowledge we could fix most any problem,” paraphrased

Bryan. “I have learned from working in the River Institute

that watershed restoration work is really community restoration!”

Tufts engineers and researchers also have taken up the Mystic

mandate. The EMPACT grant exemplifies one important approach

to understanding a complex set of water-quality concerns.

It brings together the expertise of Tufts faculty and students—John

Durant, as well as Civil and Environmental Engineering professors

Steve Chapra, Paul Kirshen, Lee Minardi and Laurie Baise,

graduate students Matt Heberger, Kim Oriel and Cristina Perez—in

addition to the city of Somerville and

MyRWA. But there are others as well. Chapra is working with

Durant, Rich Vogel and Paul Kirshen, for instance, on an EPA-funded

study of nutrient flows and management. One of only four EPA-funded

projects aimed at developing national water-quality models,

the project looks at phosphorus and nitrogen levels, chemicals

involved with eutrophication, or stagnation, caused by pollution

such as lawn fertilizers and sewage.

“The Tufts proposal did a good job of combining three

basic elements that the EPA was looking for: decision support,

basic science and measurements of a complicated system, and

the development of better water-quality computer models,”

said Durant. “When you’re developing a water model

for a water body, you have to have a good understanding of

how the system behaves. And it can be very complicated: you

have water, heat, light, carbon, nitrogen, biological matter,

and all these and other variables interacting dynamically.

We first need to develop a good physical understanding of

the river; this will be critical to the development of the

water-quality and decision-support models that will ultimately

be used by managers to reduce nutrient inputs to the system.”

Durant is also working on another project with Al Robbat in

the Chemistry Department and with the United States Geological

Survey to characterize sediment pollutants. The research includes

developing a “real time” chemical measurement

tool that could be used in the field to measure pollutant

levels in sediments.

Will the collaborative’s commitment to make the Mystic

fishable and swimmable by 2010 be achieved?

Durant is cautiously optimistic. “Realistically, some

of it will be hard to achieve,” he said. “I think

swimmable is possible. Fishable is harder because there are

stricter standards. It took 150 years to get to where we are

now. If we can simply prevent more deterioration, that would

be a victory. If we could see a reversal in the trends, that

would be another victory. If we could generate sufficient

momentum to lead us to a time where we could actually think

about using more of the river for swimming and fishing—that

would be a tremendous triumph.”

And philosophically, Durant realizes that good engineering

and science are only part of watershed solutions. “If

you want to improve water quality on an urban scale you can’t

just fix a leaky pipe,” he said.

“Science tells you what the problems are, and engineering

tells you what the solutions can be. But the community has

to tell you what they’re willing to do.”

River Advocates

How communities make informed and wise decisions, of course,

depends on developing this deeper understanding of the watershed

and how severely pollution influences or restricts recreational

possibilities. For now, MWC members agree that it’s

still too soon to know if towns and cities will realize their

stewardship responsibilities and make the best choices not

only for themselves but for future generations.

Still, the process of collaboration offers hope. Kwabena Kyei-Aboagye

Jr., regional planner in the Massachusetts Executive Office

of Environmental Affairs, has observed the workings of the

collaborative as Mystic watershed team leader for the Massachusetts

Watershed Initiative. The MWC, he said, is a good example

of how “bottom up” change can work—success

comes, traditionally, when local groups are empowered and

dedicated to the future of their communities. “Tufts

has essentially adopted the Mystic as its own,” said

Kyei-Aboagye. “The University is giving something back

to the community by working with it—and it’s doing

a great job.”

Tufts’ commitment is also noteworthy for its economic

potential; faculty can compete for and win research grants

that surpass modest state budgets. “When Tufts brings

in applied research and technical support, they help fill

in the gaps,” he said. “They bring in money that

otherwise the state wouldn’t be able to provide. Some

of the grants are quadruple what the entire annual state funding

is. That in itself is a major plus.”

Longtime volunteers like Lisa Brukilacchio, BSOT 80, a member

of the MyRWA Advisory board and the MWC Steering Committee,

adds that Tufts and MyRWA have an exciting opportunity to

establish new university and community relationships. “This

is pioneering work,” she said. “The most effective

path forward may be unclear for a while. We are asking lots

of critical questions. How do we best combine the resources

of a research university with the larger community context

to focus on watershed issues? How do we define community here?

Can we deal respectfully with the reality that most of the

area’s decision makers are white and middle class when

many of the residents reflect a more ethnically diverse population?

How do you schedule meetings to address the time priorities

of both faculty and community members? How do you balance

the mission of MWC with the visions and struggles of citizen

groups? We are just beginning to explore these questions.

We’re trying to stretch our own and other people’s

understanding of what is involved in collaborative work on

community-based environmental issues. Engaging a wide range

of players adds to the complexity and the learning involved,

but this is part of the journey toward the long-term vision

of regional ecological vitality and improved quality of life

for area residents.”

In the end, the collaboration enables Tufts and MyRWA to work

together successfully on projects that neither entity could

have accomplished alone. “The approach has created a

stronger watershed voice and is beginning to direct much-needed

public and private resources to the Mystic,” said Perez.

A case in point is a new grant from a private funder to identify

who uses the Mystic River—and why and how. “They

wanted a community recipient, but they also let us know that

they liked our work with Tufts,” she said. “We

couldn’t have gotten it if Tufts wasn’t involved.

We’ve established a solid reputation as a fact-based

organization because in part Tufts gives us an added level

of credibility. We now have a seat at the table.”

|