|

|

||||||||||||||

| Discover Act Create Hold the Mayo The Universe Within The Climb Maestro Creative Voice Mixed Media ConnectDepartments |

The Climb

Sometimes all you need to make it to the top is a few loaves of sourdough bread, the love of a good dog, and fifty extremely long catheters.Long ago, a family trip out west took us to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where we gazed upon the Tetons in all their grandeur and glory. But in focusing on the unique forms and inspiring heights of the Tetons, my eyes kept bending to the northwest, to a massive and rather cube-shaped mountain, shorter than the Grand Teton, but to me, even more impressive for the flatness of its long ridge, which led gradually up to a table-like formation at the end, hence its name, Table Mountain.

That was seventeen years ago, and I resolved right then and there that if the opportunity ever arose, I would climb Table Mountain. To be on top of it, I sensed, would be an experience deserving to be called “spiritual.” So when my wife announced last year that she needed to take a work-related trip in late August, I immediately said to myself, “Table Mountain!” and set about planning.

That meant more than figuring out where to stay and looking at maps of trails. It also meant getting my mind ready to take on this adventure, which offered risks, given my aging body, the height of the mountain (eleven thousand feet), and the fact that the mountain rests in a wilderness owned not by humans but by sudden storms and bears. My planning included reading up on how to use pepper spray if attacked by a bear, and also on John Muir, the nineteenth-century naturalist and founding father of the Sierra Club.

Muir became my appointed guide, not primarily because he was a world-class mountaineer, scientist, and writer who inspired our nation to preserve the wilderness, but because his spirituality spoke to me. Using biblical language to express his own unorthodox religious perspective on the human-nature relationship, Muir celebrated the wilderness as “unfallen” and “Godful” and invited all of mankind to leave their petty concerns behind in the city and to come to the wilderness to be healed and saved. In wild places, he found sacredness everywhere—in rocks and waterfalls, in flowers and wind, in birds and mammals, but most of all in mountains, which he referred to as “God’s cathedrals.” Sourdough bread was what Muir took on his hikes in the Sierras. I intended to do the same in the Tetons and to feel that sacredness that Muir would surely have felt when being up there on the ridge of Table Mountain.

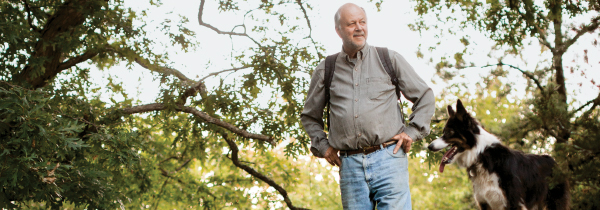

One of my favorites among Muir’s writings is his account of his night with the dog Stickeen out in a storm on a glacier in Alaska. If ever man and dog proved good companions under extreme conditions, it was Muir and Stickeen on that glacier. On my pilgrimage to Table Mountain, I would be taking Abby, my border collie, and I hoped that she and I might make similar companions.

I’ve had border collies before but nothing like Abby. Because of their strong herding instincts, athleticism, and intelligence, border collies can be a handful, but in Abby’s case, it was more like several handfuls. Having Abby as my companion was like having a three-year-old child who is also a world-class athlete driving a Ferrari. On our walks in the woods, Abby spent most of the time running ahead of me and out of sight, only to magically come racing up the path from behind and then pass me like some express train barreling past the passengers waiting on the station platform. Still, almost everyone who came into contact with Abby loved her. On our walks in the woods, others would see her, smile, and yell out “Abby!”

In preparation for our plane ride, I rigged a rolling platform to transport Abby’s crate through airports and onto the cargo section of the plane. My preparations were moving along nicely. Still, I was going to have to deal with a minor operation that I’d planned to have when I finished teaching in the summer. After the operation, I was going to have only ten days to get in good enough physical shape for the climb, but I had put the procedure off for too long, so ten days would have to suffice. What I hadn’t figured on was a side effect from the operation, namely, a retention problem, the details of which I will spare you.

To solve the problem temporarily, I was equipped with a bag. Ordinarily, that wouldn’t have been a big problem, but how in the world was I going to climb Table Mountain with a bag? And if I could, would I even want to? These questions haunted me up until two days before the planned departure, when, in desperation, I called a urologist friend of mine, explained my problem, and heard with surprise and relief, “Don’t worry. Come to my office in the morning, and I’ll fix you up so you can take your trip.”

He fixed me up all right—with fifty or so extremely long catheters that freed me from the bag…but left me with an astounding alternative process, the details of which I, again, will spare you. Anyway, those catheters accompanied me throughout the trip—into airport men’s rooms and Idaho cabins (where I hid them from the cleaning lady lest she find them and think they were drug paraphernalia)—and when I was climbing, they were always in my backpack. Though they were all part of making this a “high” adventure, I would have preferred an electrical storm.

And so, on the day of our trip, and equipped as we were with a rolling crate, my catheters, and plenty of sourdough bread, Abby and I flew from Boston to Salt Lake City, Utah, where I had rented a car to drive north to Driggs, Idaho, a small town two miles from the western border of Wyoming and only six miles from the trailhead for Table Mountain.

The four-hour drive was taken up largely with me listening to radio preachers. On road trips, when I am driving alone, I make it a practice to listen to radio preachers, most of whom lead the many evangelical faith communities that dot the American landscape. Evangelical radio preachers can inspire in ways that many preachers from so-called mainline Protestant faith traditions do not. They do so, in part, because of their strong convictions and the power in the way they tell stories. They tell Bible stories like no others tell Bible stories, so that we are right there with Jesus, his disciples, Mary, Isaac, Joseph, and the host of characters that populate the Bible. We listeners become moved by the humanness and divineness in life, by the folly and limitations of our doubts and anxieties, by the hopes that spring eternal, and by the essentially religious meanings that can help us cope.

Using a rented cabin as a base, I spent two days trying to get myself in shape for the climb up Table Mountain, hiking a long wilderness trail in the valley below, one that afforded short climbs to plateaus on the side. And though I was out of shape, the wilderness re-energized me enough to feel ready to climb.

On the day of the climb, I rose before dawn, packed water and sourdough bread, some food for Abby, and a can of pepper spray, and the two of us set out on the six-mile drive to the trailhead. As we drove over the country road and into Wyoming with just enough light to see the summit of the Grand Teton looming majestically at the end of the valley, a large deer trotted in front of us—paying no attention to us and seemingly undisturbed by our presence. I took this deer to be a good sign—as I usually do on early morning walks when meeting up with a wild animal, a deer, a blue heron, even a snarling fisher cat. They leave me optimistic about the rest of the day. And so, when Abby and I set out on the trail up Table Mountain, I had high hopes and a sense that the day would go well.

About an hour into the long ascent toward Table Mountain’s headwall, I sat down by a stream to take in the view. At such times, Abby usually plays in the water and snoops around for places to dig. But after a while, I noticed she was gone. I called her but got no response. I knew right then that she was out of earshot, and though back home Abby had run from me many times in the woods, this felt different: I had no idea of the territory, and there were bears. So I prayed.

Prayer has always been part of my life, not because someone taught me to pray, or because others around me were praying, but because there were crises that required me to go to the highest court for help. My first crisis warranting extended conversations in prayer with the Creator of the universe occurred in the Fifties, when I was ten. It involved the poor performance of the Baltimore Orioles baseball team, despite the team’s trying very hard. To me, at ten, this seemed terribly unjust. That players should try so hard and continue to fail was my first experience with the age-old question “Why do bad things happen to good people?”

So right there on Table Mountain, having lost Abby, I prayed. I reminded the Creator of the universe of Abby’s divine spark, of my love for her, and of our being well-matched—all good reasons for Abby and me to be reunited. My praying helped me to keep going, for almost four hours, all the way to Table Mountain’s mile-long ridge.

There, on that ridge, the glory of the Tetons suspended my despair. At that moment, I had the experience I had anticipated some seventeen years before, an experience of being not on top of the world, but rather in the world, a world that is vast and diverse and beautiful, a world that is neither made by nor dominated by humans, a world where, in fact, over most of its history, humans didn’t even exist.

Up there, I could feel the enormity of time. I could see in front of me the results of events that occurred 30 to 60 million years ago, when the Tetons were pushed up as the earth split along a north-south fault line, and as the western side rose to form the mountains while the eastern side sank to form the valley. And all around me was a wondrous panorama, one that stretched for miles. I have never felt so happy for feeling so small as I did up there on that ridge on Table Mountain. I was momentarily freed from the persistent and universal delusion that we humans are the center of the universe and lords over earth and animals.

But my happiness was short-lived, as I returned to despairing over Abby. Complicating matters was the fact that halfway up the ridge, the mountain’s other, much steeper trail met up with the one I was on. I feared that Abby might have descended that other trail in search of me, and so I camped myself at the crossroads and waited, asking the occasional climbers passing by if they had seen her.

After what seemed a very long time, I heard a group coming down the trail from the summit. When they came in sight, there was Abby happily trotting along as if nothing was amiss. When she spotted me, she ran to me wagging her tail, as if she was telling me about the great time she had had at some party. In fact, that seems to have been the case, for I learned from the climbers that she had gone to the summit, where she had made the rounds greeting everyone and where she had become an instant celebrity.

My joy at being reunited with Abby outweighed any lingering frustrations I felt toward my prodigal companion. She was with me now, and that was what mattered. In fact, she was almost too much with me. On the long trip down the mountain, which took until sundown, she stayed about two feet behind me, even when we passed a tiny moose grazing near the headwall, so that at times I had to shoo her away. Maybe she had been more anxious about being separated than I had thought.

Abby and I made it back home and in subsequent months had other adventures, including being caught in a snowstorm on top of Mt. Washington and spending several hours wandering in the dark after getting separated on a walk in the Fells Reservation near Tufts. But nothing has compared to the pilgrimage to Table Mountain. I carry the memory of that pilgrimage with me everywhere, and it helps keep me focused on what matters most, especially on our connections to the natural world and on our being the center not of the universe, but of the lives of those we love, including those with furry tails.

W. George Scarlett is a senior lecturer in and deputy chair of the Eliot·Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development. He is also general editor of the forthcoming SAGE Encyclopedia of Classroom Management.