|

|

||||||||||||||

| Discover Act Create ConnectRemembering Fred Time and the Hour Miracle on College AveA Space for Next-Gen ThinkingCharacter Sketch Great ProfessorNewswireHead of the Class The Big Day Departments |

Time and the Hour

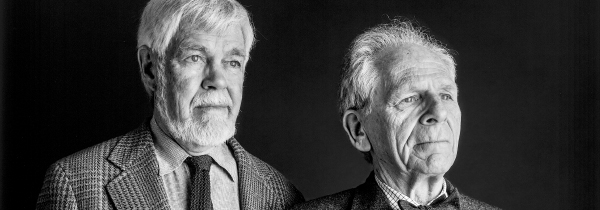

In memory of Sylvan Barnet, the renowned Shakespeare scholar and beloved Tufts professorIn the spring of 1954, the three newly minted Harvard English Department Ph.D.s had their choice of plum assignments: it was the Golden Age of American higher education, that brief window after World War II when the soldiers came back from the fighting and were pouring into colleges and universities. To accommodate them, campuses were opening and expanding across the country. Clark Kerr created dozens of new schools all over California. Nelson Rockefeller did the same in New York State, with SUNY and CUNY. The enrollment “ethnic quotas” that had been established in the 1920s and 1930s had finally disappeared, and the three young Ph.D.s, a Catholic and two Jews—all of them veterans—had met at Harvard in English. And they wanted nothing more than to stay in Boston and be with each other. They were the “Three B’s”: Sylvan Barnet, Mort Berman, and Bill Burto. This was a friendship for all times. Bill eventually settled on a job at Lowell State, while Mort landed at Boston University. As for Sylvan. ...

Well, Sylvan died in January. You may have seen the tributes, including the one in the New York Times. Sylvan lived a remarkable life, filled with love, joy, learning, and passion. But back in 1954, when he interviewed with Tufts English Department Chairman Harold Blanchard, he was just getting started.

Immediately after that interview Blanchard knew that he had found his man. Sylvan, just twenty-eight then, came from the correct graduate department—in English, Tufts hired exclusively from Harvard. He was the right gender—in English, Tufts hired only seemed to be a “safe” name. The tenured members of the Tufts English department were exclusively Harvard, male, white, and Protestant. The young man even wore a bow tie: perfect. He would contribute to the harmony in a department that was homogeneous, collegial, and generally mediocre. All of that would soon change.

Within ten years, the Three B’s were all chairmen of their departments. They were the ones now doing the hiring, and they would pile onto a table the job applications they received, first in their house on Trowbridge Street in Cambridge, then on Ash Street near Harvard Square. In the 1960s you might have applied for a job at BU, but received a reply from Tufts, or perhaps you wrote to Lowell State and got a return letter from BU.

At Sylvan’s urging, the three men began writing together in the 1950s, and they became legends. Their text editions, writing guides, style manuals, and literary anthologies sold in the thousands of copies all over the country. Their editions represented the largest adoptions of any first-year writing guides and literary anthologies in the country. Sylvan also wrote and edited books of his own—most notably the Signet Classic Shakespeare series—spreading the Tufts name from Washington State to Florida, from Maine to California. The Tufts Tisch Library has forty books edited either solely by Sylvan Barnet or with collaborators.

In 1963, with their newly accumulated wealth, Sylvan and Bill began collecting Japanese art, especially calligraphy. Today their collections can be found at the Freer Gallery in Washington, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and Harvard. In 1981, Sylvan sent off the first edition of A Short Guide to Writing About Art. In the last months before he died he completed work on the eleventh edition.

But above all he loved to teach. His Shakespeare course was the stuff of legend. Sylvan was a performer, at times taking off his jacket, putting it on backward, and, as his hundreds of students cheered, imitating Boris Karloff’s walk in the movie version of Frankenstein. He was the consummate lecturer, even as he led his English 1-2 class by making jokes about adverbs while teaching first-year students to write. I often sat, watched, and learned.

It was 1984 when he came to my provost’s office to announce that he was going to retire. Bill was resigning from Lowell, Mort was being driven out of BU by John Silber, and now was the time, he said, to smell the lotus blossoms. For the next three decades he continued writing about art, editing his books, traveling to Japan, and talking to anyone who came by the house on Ash Street, always demonstrating the same wit, charm, and brittle humor that made his classroom unforgettable. When Bill Burto died in 2013, the art world mourned, and Sylvan wept. He then wrote and gave to me his own obituary (see page 68), which included the epitaph, written more than three centuries earlier by Sir Henry Wotton, “Upon the Death of Sir Albert Morton’s Wife”: He first deceased; she for a little tried/ To live without him, liked it not, and died. Even as he retreated into sadness, he continued to welcome old and new Tufts friends alike, and also the Tufts students, some from fifty years ago, who would come to pay homage, or telephone just to hear his voice. To the end, he loved conversation, gossip, ice cream, Southern barbecue, and good Chinese food. His friend and colleague Marcia Stubbs would bring lamb chops sometimes. Two days before he died, I brought ice cream, but he was sleeping. Then he finally joined Bill. Sylvan was eighty-nine in December. In his many decades at Tufts, he never stopped teaching, and I never stopped learning.