|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

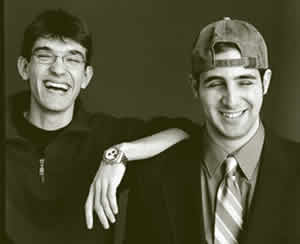

COVER STORY: A Political Pair

|

|

|

Photo by Mark Ostow |

| |

By Michael Blanding

Good

friends and sparring partners find themselves on opposing sides

of the political debate

Adam Blickstein and Philipp Tsipman have barely sat down at

the long table in the Executive Room on the second floor of

the Mayer Student Center before they start in on each other.

“I’m not a huge fan of high school or collegiate

politics,” says Blickstein, the outgoing head of the Tufts

Democrats. “It’s more of a way for people to get

their faces out there than to talk about substantive issues.”

“We talk about substantive issues,” protests

Tsipman, outgoing president of the Tufts College Republicans.

Before Tsipman can continue, Blickstein overrides him. “Even

this ‘academic integrity’ thing [the grading of

students’ work without regard to their political philosophy],

I think it’s more of a chance for people to promote an

ideology than to promote a genuine predicament that students

face.”

“Ouch, ouch!” cries Tsipman,

for whom “academic integrity” was a signature issue

on campus.

Blickstein knows this, of course. The two have been sparring

on campus for the better part of four years, and the Democrat

has used the issue to score a point right out of the box.

“When they told me we were meeting in the Executive

Room, they said, ‘Don’t tear it apart,’”

Blickstein later jokes. In reality, the two politicos are good

friends, and—as they sit down for an informal debate on

the eve of their graduation—they swear that they have

a lot in common. Both are of Russian-Jewish descent, for instance,

and both refer to themselves as moderates in their respective

parties. Tsipman even says that the two “agree on a lot

of things.” What those things might be, however, is up

for debate, as is everything else between these two Jumbos.

In the views they express—on the Iraq War, cutting taxes,

gay marriage, and military spending (to name just a few of the

topics we cover)—they reflect the wider political divide

that has split the country into Red and Blue, and made this

the most contentious and partisan election year in memory.

A lot has happened in the four years since the two matriculated

in 1999, from the Florida recount to the terrorist attacks of

September 11, 2001, to the subsequent military campaigns in

Afghanistan and Iraq. Those events, they say, have scaled the

ivory tower, and broken students somewhat out of the apathy

that has famously gripped them for years. “It sounds really

cliché, but what’s going on in [student] politics

now goes back to September 11,” says Blickstein. “It

really did change things.”

“It affected

our generation a lot,” says Tsipman, adding, “It

made people much more aware of what’s going on in the

world and the importance of government and politics in their

lives.”

“It was a binding agent,”

says Blickstein, “but it was also a wedge.”

Both students remember the surreal experience of going to class

after the planes hit the Twin Towers and seeing politics and

patriotism percolate into the classroom. When Blickstein went

to his Modernist Writers class, for instance, he says that he

was surprised by the sudden pro-America views of his professor,

who was “no fan of Bush” before the attacks.

As the momentum gathered for the Iraq effort, however, a split

was clearly evident on campus, with the most vocal students

and faculty protesting the war. “You had some professors

still coming out of their experiences in the 1960s,” says

Tsipman, who helped lead a rally to support the troops earlier

this year, and says he has seen committed support for the military.

“There is a tremendous support for bringing back ROTC,

which was voted out by the faculty after the Vietnam War,”

he says.

Blickstein is himself dismissive of some anti-war protesters,

whom he sees as being more interested in grabbing headlines,

but he agrees with their critique of Bush. “You see the

same kind of rhetoric, the same massaging of information going

on there as went on during the Vietnam War,” he says.

“As young people, as Americans, we are obligated to look

at the situation and make a decision for ourselves if what is

going on there is right.”

From outward appearances, it’s hard to guess which of

the two students is the Republican and which the Democrat. Tsipman

shows up in a T-shirt, flannel shirt, and jeans, while Blickstein

wears a sweater and khakis more befitting a political aide.

The outfits reflect their personalities. Blickstein is always

ready to pounce, frequently interrupting his colleague to correct

a partisan statement. (“If you haven’t noticed,

I like to talk a lot,” he acknowledges.) Tsipman, meanwhile,

sits back in his seat, and chooses his moments and his words

more carefully, almost visibly slowing down the conversation

as he builds his arguments.

Tsipman was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and moved to Brookline,

Massachusetts, with his family in 1995. His family was apolitical,

he says, and he might have been too if it weren’t for

a high school project he did on the discrimination against Jews

in Russia after World War II that made him realize how events

such as the Holocaust and the Cold War had affected his family.

“The whole thing made quite an impression on me, just

understanding how politics can affect people’s lives.”

Though he started out volunteering for environmental causes

and Amnesty International, he became disillusioned by the attitudes

of liberals around him, which he said “did not match reality.”

After a teacher compared Ho Chi Minh to George Washington, he

says, he began actively embracing more conservative viewpoints.

He didn’t find many of those at Tufts, where only six

percent of students are Republicans, but he and his fellow conservatives

have done their best to diversify the opinions on campus. “We’re

in the papers more than the Dems,” he says proudly. Through

the ongoing “academic integrity” campaign, the campus

Republicans hope to institute a formal process by which students

can appeal grades that they believe have been influenced by

their professors’ political biases.

For Blickstein, the difficulty has not been in countering the

prevailing view on campus, but in motivating the majority of

liberal Democrats who are politically disengaged. Despite the

increasing amount of political activism in the past four years,

he says that the majority of students are still too preoccupied

with their studies to care much about the larger world. Though

the Democrats have 500 students on their mailing lists, they

are lucky if they get 50 people to a meeting.

“If

you are in the majority, there is no impetus to fight for your

cause,” he says. “Students say, ‘What’s

the point of being loud and vocal if the majority of the campus

agrees with me?’”

Blickstein traces his own interests in politics back to his

family, which unlike Tsipman’s, was actively political.

His grandmother, a staunch Republican, worked for the governor

of Pennsylvania. A cousin was deputy mayor of Philadelphia (and

a Democrat). As for him, his own political epiphany came in

fifth grade, while he was growing up in Rochester, New York,

when he and a fellow student got into a debate about Ross Perot.

“You’d like to think that it was some kind of profound

political discussion,” he says, “but I pretty much

just thought he [Perot] talked funny.” His political instincts

were further honed in high school when, as secretary of his

class, he engineered an impeachment of the class vice president

after he had been caught drinking at a football game. “I

knew if we kicked him out, I would ascend to the level of vice

president,” he says, “so there was a bit of Machiavellian

puppetry there.”

In addition to the war, Blickstein says that students have gotten

energized by the current national battle over culture. “Iraq

is definitely the preeminent issue,” he says, “but

underneath that is the social war that’s going on that

kind of crept up on us.” Tufts students have been active

on the gay marriage debate at the State House as well as the

abortion issue, fielding a large contingent at the Women’s

March in Washington this spring.

Tsipman has also joined the larger debate on indecency while

at Tufts. When he says a school-sponsored “safe-sex”

tutorial crossed the line into lewdness, he and the college

Republicans publicly complained to the dean, and made the local

Medford paper. “This was the university putting this on

at the Student Center. It was very explicit,” he says.

For Blickstein, such debates are almost behind the times, as

he sees young people becoming increasingly liberal on social

issues. “If you want to live in the 1950s, I think we

should stay in the 1950s, but I think a lot of what America

debates about—abortion, indecency on television—is

anachronistic. You have this social tidal wave coming; this

conservative backlash against homosexual rights and indecency

is just trying to postpone the inevitable.”

Tsipman counters, “We’re not trying to go back to

the ’50s, but we’re not trying to go back to the

’60s, either.” He claims polls say that many college

students are actually more socially conservative than the last

generation. “They see the excesses of their parents’

generation, the divorce rates, and the drugs,” he says,

“and that’s not quite where they want to be themselves.”

Politics play a role in both students’ graduation plans.

Tsipman, who has already formed the Tufts Republican Alumni

Coalition, has landed a job as field director for Rod Jané’s

Massachusetts state senate campaign. Blickstein, meanwhile,

who’d like to get into political reporting, has landed

a freelance position at CNN’s Washington, DC, bureau.

And both are supporting their party’s choices in the coming

election.

I ask them to give a stump speech for their respective candidates.

Like good politicians-in-training, both of them go negative

before touting their own man.

“If you look at

what is going on in America right now, it’s going down

the wrong road on a number of issues,” says Blickstein,

“but the big ones are Iraq and economic stewardship. I

think people are starting to lose trust in the Bush administration

and their continued rhetoric that creates false realities, false

perceptions, false ideas, and false hopes. The Kerry administration

will do the exact opposite—listen to the people and create

an economy that emphasizes a balanced budget and spends money

where it needs to be spent.”

Not to be outdone, Tsipman counters, “I don’t think

John Kerry presents the ability to lead the country in any direction.

His record of changing his stances and decisions is going to

come out very clearly, and the people of this country are going

to see that this guy has no plan to lead us anywhere. The Bush

administration showed strong leadership in the face of terrorism

and on social and economic issues. They are providing a course

for America to a better future for our generation and our children’s

generation.”

He has barely finished when Blickstein jumps back in, saying,

“That’s the same superficial argument that Bush

gave last night. You’re really toeing the party line.”

Tsipman just smiles at him, shaking his head at his friend’s

attempt to score a last point.

Says Blickstein, “I always have to get the last word.”

Michael Blanding is a senior writer

at Boston Magazine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|