|

|

||||||||||||||

| Discover Growing the Stuff of Life ZZZT! Your New Nose Is Ready Wisdom from 1924 Character Sketch Health News from Tufts Act Create ConnectDepartments |

ZZZT!

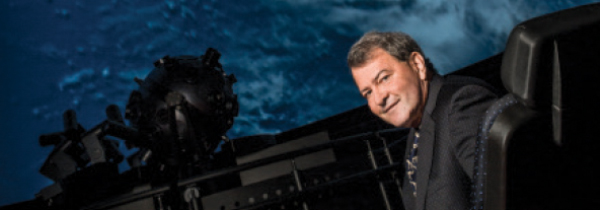

There’s electricity in the air at Ioannis Miaoulis’ Museum of ScienceFor half a century, a very toothy Tyrannosaurus rex has awed visitors to Boston’s Museum of Science. Updated in 2001 to correct anatomical flaws, this giant of the Mesozoic towers feet away from a much newer exhibit about nanotechnology, the science of the super small. What a clever way, I suggest to Ioannis Miaoulis, to juxtapose such symbols of the museum’s two primary worlds, the natural and the designed. Miaoulis, the museum’s director and president—and the former dean of the School of Engineering at Tufts (he’s also E83, G86, E87, E12P, E15P)—will discourse at length on ways to better advance science and engineering, but he demurs on this particular alignment. “Some things we do are on purpose, and some things are by necessity. T. rex is just too big to move.”

But Miaoulis, who wrought major changes to engineering instruction at Tufts, is moving to further transform the Museum of Science. Founded in 1830 as the Boston Society of Natural History, the museum has become Boston’s most popular cultural attraction, with 1.4 million visitors a year.

It just completed a $250 million capital campaign. And this past June, Miaoulis outlined a ten-year plan to museum trustees to improve the visitor experience with a series of physical and other changes in the domed building on the Charles River that opened in 1951.

But while his passion to advance technological literacy harkens back to his years at Tufts, his current post presents him with an even greater challenge, one common to all museums: how to hold the interest of generations of young people hooked to tiny screens and even tinier attention spans. Can the Boston Museum of Science—with brick-and-mortar halls and exhibits that those kids’ grandparents may well have seen—remain “cool” enough that young people will want to visit beyond obligatory school field trips?

In a way, Miaoulis has reached an institutional pivot point similar in scale to that faced by a legendary predecessor, Bradford Washburn, the mountaineer and nature photographer who headed the museum for forty years beginning in 1935.

“Washburn inherited a stale museum that was all natural history, no physical science or life science and, of course, no engineering,” says Miaoulis. Washburn added physical science, and introduced more participation along with observation. “Now,” Miaoulis says, “we want to focus more on the process of discovery and give context to how it fits into your world and your life.”

Doing so in an instant-gratification world is tricky, as Kirk Johnson, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, knows. “Museums have always catalyzed curiosity and interest,” Johnson says. “Our technological and other abilities keep racing ahead, but our ability to keep people interested in how these things actually happen is not keeping up. How we learn and give information is fundamentally changing. The first real wave of digital natives is coming online and mobile devices are ubiquitous. The saga of the Museum of Science is that of a very venerable organization still trying to think about where it’s going and how.”

As a boy in Greece, Yannis, as most people call him, enjoyed fishing and stargazing in the Bay of Corinth. His father was a civil engineer, but Yannis wasn’t exactly headed down that career path. As a teen, while attending the best K–12 school in Athens, he was eager to switch from being a boarding student to being a day student. He got his wish, but in the process he discovered “freedom and girls.” He flunked four courses, including math and physics. “I knew I had to intercept my report card before it got to my dad,” he says, “or I would be right back in boarding school the next day.” He asked his father’s secretary to “disappear” the report card. “She made me a deal. If I got four A’s the next semester she wouldn’t say anything about it. I ended up getting those A’s, including in physics. My teacher was shocked. I was not born an engineer—it came by necessity.”

Miaoulis enjoyed applying the lessons he was learning. He started by building a small-scale solar desalinator and later designed a solar heating system for the school swimming pool. He planned to attend college in Greece, but his godfather urged him to find an engineering school within a liberal arts environment and pushed the United States. After doing some research, Miaoulis decided he wanted to be in Massachusetts, and chose Tufts, which offered him financial aid.

He graduated a year early from the School of Engineering in 1983 and received a master’s at MIT the following year. He returned to Tufts to earn a master’s in economics in 1986 and a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering in 1987, the same year he was given a tenure track appointment as an engineering professor. Miaoulis became the engineering school’s associate dean in 1992 and dean a year later.

Miaoulis maintains close Tufts ties. He is an alumni trustee, and his two daughters have graduated from the university with engineering degrees, the youngest just this May.

It was during his years at Tufts that Miaoulis became an evangelist for outside-the-box approaches to explaining and teaching science and engineering. Before he became dean, the engineering school was losing about twenty-five percent of its freshmen to liberal arts, he recalls. “We had focus groups in the dean’s lounge and asked why. The answer was basically ‘We don’t find engineering interesting.’ ” Miaoulis drew on his own passions to spice things up. Thermodynamics, for example, was “one of the most dreadful courses in engineering. Everyone hated taking it and everyone hated teaching it,” which, as a new professor, he was assigned to do. “We ended up making it one of the most interesting courses in engineering by adding things like teamwork and hands-on projects.” And long before fancy chefs became America’s new priesthood, Miaoulis, quite a cook himself, created a course called Gourmet Engineering, using a fully equipped kitchen to teach concepts such as heat transfer. That and other new courses became hugely popular.

“In general, science and math are taught in unattractive ways at all levels, from grade school to college,” says Miaoulis. “The science curriculum in our schools tends to be about the natural world, not the designed world, even though the world around us is almost all designed.” To help rectify that imbalance, Miaoulis and Tufts worked to have engineering taught in parallel with science in Massachusetts public schools. “It was my life goal to introduce engineering into every classroom by 2015. We’re not there yet, but we’re getting pretty close.”

Miaoulis set that somewhat arbitrary target date while still at Tufts. But then he got a call in 2002: the Museum of Science was seeking a new president, and its board wanted someone who would give engineering equal status with science. “When the search firm called me, I said, ‘I love the museum, but my heart and my whole life is at Tufts,’ ” he says. But the possibilities of this new job quickly grew on him. “To everyone’s surprise, I was gone in two weeks. It just made sense because of everything I was doing to make these subjects exciting and accessible to people. What better place to make science fun than in a science museum?”

Miaoulis oversees an operation with a $60 million annual operating budget and 357 full-time employees. There are also hundreds of red-coated volunteers, who offer visitors Mr. and Ms. Wizard moments through seven hundred interactive exhibits scattered across the sprawling museum. They range from up-close encounters with live animals to the Hall of Human Life, a 10,000-square-foot smorgasbord of life science exhibits, displays, and interactive technologies and experiences.

Wandering into the Engineering Design Workshop, I observe a father and young daughter having fun with “Whirling Windmills,” where participants test changes in a wind turbine’s blades. “Try decreasing your angle a little bit,” suggests Dad. The girl tweaks her propeller-like assembly and repositions it in front of a floor fan. As the fan spins the blades, the needle on an attached meter moves. “Look at that,” says Dad. “You’re up to one point three volts now. Not bad.”

In the Theater of Electricity, adults and children alike watch transfixed as a museum educator powers up the forty-foot-tall, 2.5-million-volt Van de Graaff generator built in 1931 and given to the museum by MIT. With a mix of showbiz and solid science, he explains the basics of electricity, capping off the demonstration with crackling bursts of real lightning. As I look around, even the three teenagers sitting next to me have stopped texting.

That wow factor is one of the key draws of a science museum. “Where else can you see lightning so close up?” asks Miaoulis. Or dinosaurs. “You cannot compare anything you do with an electronic device to standing under a triceratops.” Then add the social interaction among visitors. “If done right, museums are going to beat the handhelds,” Miaoulis declares.

Walking around the museum’s sometimes confusing layout (something the ten-year plan will target), I spy lots of signs pointing out spots to take selfies but few displays linking directly to smartphones. That may seem surprising in an institution that celebrates technology, but it reflects a careful dance by science museums with the so-called cutting edge.

Victoria Cain, a Northeastern University historian and coauthor of Life on Display: Revolutionizing Museums of Science and Nature in the United States, puts it this way: “Apps are profoundly individualistic, private experiences, whereas much of the learning in a science museum is ultimately a social activity, in public, between you and a docent, you and a friend, you and a parent.” Not only that, she says, but we are physical beings. “People like to touch things, and learn from manipulating things or petting the hair on an animal specimen. Those multisensory moments remain seared in people’s memories.”

In a time when science denial extends high into the halls of Congress, museum officials are keenly aware of the role their institutions play in helping to educate a public that thinks the truth is always a few clicks away. Says Johnson, at the Smithsonian: “We’re not doing the best job of creating a population ready for the next century, and I suspect that Bradford Washburn would feel the same way.”

Miaoulis agrees. It’s why he continues to build on work he began at Tufts to expand the pool of next-generation engineers, inventors, and scientists, especially to more females and people of color. Shortly after taking the helm at the museum, Miaoulis launched the National Center for Technological Literacy, an effort to promote technology and engineering in science museums and schools across the country.

But he also knows that museums need new approaches and exciting exhibits to compete for the hearts, minds, and clicks of the young. So in late June, the Museum of Science turned to Buzz Lightyear, Dory, WALL•E, and other Pixar characters to reach fans of the company’s hit movies. The Science Behind Pixar exhibition will run in Boston for six months before heading to other museums.

“We’ve become good at taking a topic that is exciting because of pop culture and giving it real science and math,” says Miaoulis. A Star Wars exhibit created by the Museum of Science, for example, broke attendance records everywhere it traveled. “What attracts people to places like ours is a combination of education and entertainment,” he says. “Most people don’t want to go to school on a Saturday, but they do want to have fun, and they do want to learn.”

While Miaoulis hopes Pixar and similar exhibits will turn visitors on to science and technology, he also sees them as a way to help the public distinguish between ideology and data-driven science. “If we are serious about solving major problems such as climate change, it starts with helping people understand and talk about them,” he says. “And that’s what a good science museum can do.”

PHIL PRIMACK, A70, is a freelance editor and writer in Medford, Massachusetts.