|

|

| Nicki Sobecki, A06 |

Express Yourself

Spray paint and a cannon spell a long-lasting

tradition at Tufts

by Michael Blanding

It’s the night before spring finals and three shadows steal across campus under the cover of darkness. One of them is carrying a white shopping bag that clinks against her leg. Once at the top of the Hill, she distributes cans of blue spray paint. One by one, the women step up to their target: an antique cannon embedded in a base of concrete.

“What should we write?” asks Erika Wool. “We could write something like ‘Good luck on finals,’” says Emily Parker. “We could write something political,” says Samantha Hilbert. “What do we all agree on?”

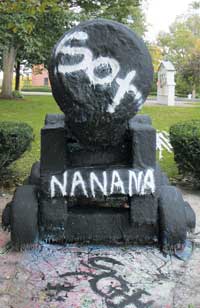

It’s a question that many Tufts students have pondered as they partake in a nocturnal Tufts tradition that always invites youthful imagination. Painting “the cannon” is a rite of passage. The form has been sandblasted twice since the 1970s to remove successive coats of paint that drip-dry off its barrel like so many multicolored icicles.

For the alumni who have painted it over the decades, the very impermanence of their messages makes the act a poignant expression of their time on campus, a tabula picturata carried down only in stories, pictures, and half-remembered images.

|

| Nicki Sobecki, A06 |

“Tufts is one of those places where a lot of groups have their own traditions, but the cannon is one of the only campus-wide traditions,” says Wool. “It’s something you need to do if you are going to have the full Tufts experience. Anywhere else it might be vandalism, but here it’s tradition.”

Rumors have circulated about the cannon for years: that it was one of the original 24-pounders from the USS Constitution; that it was given to commemorate Tufts’ win over Harvard in the first football game ever played; and that its muzzle was positioned to point in the direction of Harvard. University archivist Anne Sauer, J91, G98, says that it is difficult to trace the origin of the tradition. “Things like the cannon don’t get documented anywhere,” she says. “Everybody knows about it, but trying to find hard and fast sources is almost impossible.”

As she has been able to piece together, the cannon is actually a replica of one from “Old Ironsides.” It was given to the city of Medford by the National Park Service as a token of appreciation for money raised by schoolchildren to restore the historic ship. Medford, in turn, gave the cannon to Tufts in 1956, when it was mounted overlooking the slope of the Hill on a small lawn between Goddard Chapel and Ballou Hall.

|

| Nicki Sobecki, A06 |

The cannon’s early history on campus was an eventful one. When it was removed for restoration in the mid-1960s, student sentiment against the Vietnam War succeeded in keeping it from being re-placed. A group of alumni later lobbied to return it. Then in, October 1977, a group of students painted it, for probably the first time, in protest of an honorary degree conferred on Imelda Marcos, the wife of Philippines president Ferdinand Marcos. It was quickly repainted by a student opposed to the vandalism—and the tradition was born.

Over the years, the cannon has been painted almost nightly, with a variety of messages that range from the personal to the political. It has been used as a bulletin board to announce coming events, declare school spirit, and confess personal puppy love. It has even been used for marriage proposals and for announcements of weddings at Goddard Chapel. A group called the Monty Python Society has also been particularly creative in its cannon runs, once covering it entirely in tin foil, and another time in Saran Wrap with cans of Spam wrapped around the muzzle.

Not that the tradition has been without incident. After September 11, 2001, the cannon displayed the single word “peace” for several weeks. Then, on the eve of the bombing of Afghanistan, several members of the publication Primary Source painted over it with an American flag. That night, three members of the Coalition for Social Justice and Nonviolence got in a tussle with the publication’s editor, earning them disciplinary probation (later reduced to a warning).

|

| Laura Ferguson |

This night, the cannon is the focus of less serious stuff. The three women have done this before, as pledges for their sorority, Omega Chi. The rules, they explain, are simple: The cannon may only be painted at night, and must be guarded until sunrise to prevent usurpers from coming and painting it out from under you.

On the night of their previous experience, they pitched tents and slept out in the bitter cold. “It was definitely a bonding experience,” says Hilbert. “Sitting up here for four hours we got into all kinds of discussions.” Not that they were alone. Campus police officers came by, not to read them the riot act, but to help them keep watch. Fraternity brothers brought them hot chocolate.

Back on the Hill, the women have decided on their message and set about memorializing it with silver writing. As a final touch, they paint the mouth of the cannon silver as well. Tomorrow, the cannon may carry a different message, but for tonight at least, it blasts: “GOOD LUCK ON FINALS” on the left, and “ COLLEGE AVE 05-06,” on the right. They admire their handiwork. “Next time I’ll wear clothing I don’t care about,” says Parker. “I wonder,” muses Wool, “if it will ever just become a mound of paint.”

|