|

|

||||||||||||||

| features A Tough Pond to Fish House of Israel The Kindness of Animals To Better Society A Life in Shoes think tankplanet tufts newswire the big day departments |

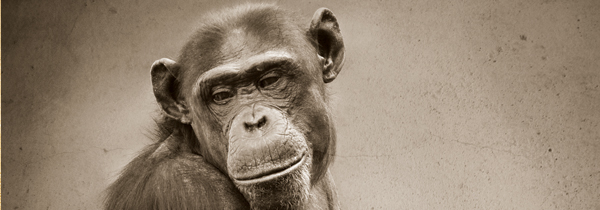

The Kindness of Animals

Nature, not necessarily red in tooth and clawOne day at the Twycross Zoo in England, a bonobo (or pygmy chimpanzee) named Kuni watched a starling fly inside her enclosure, hit a clear pane of glass, and drop to the ground. As the primatologist Frans de Waal relates in his book Our Inner Ape, Kuni went over, picked up the feathered lump, and carefully tried to place it upright. The stunned bird didn’t respond. Next Kuni gave a toss, which resulted in some ineffectual fluttering. Then she picked up the bird once more and climbed to the top of the highest tree in her enclosure. Up there, high and swaying, holding on with both feet, Kuni used her hands to grasp the bird gently. She opened up the bird’s wings and once again gave a toss—and the bird flapped and fluttered and, finally, fell. Kuni descended from the tree and stood guard over the unmoving creature, not allowing any of the other bonobos to approach. At long last, the starling recovered sufficiently to fly away. “The way Kuni handled this bird,” de Waal remarks, “was unlike anything she would have done to aid another ape. Instead of following some hardwired pattern of behavior, she tailored her assistance to the specific situation of an animal totally different from herself.”

Such kind, caring behavior from a mere ape, a “dumb animal,” would no doubt confound many who subscribe to the popular version of Darwinism, passed down to us by Darwin’s colleague and chief defender, Thomas Henry Huxley. In his 1894 lecture “Evolution and Ethics,” Huxley memorably summarized the concept of evolution as a struggle for the “survival of the fittest,” employing a phrase Darwin had earlier borrowed from the English philosopher Herbert Spencer. It was a catchy phrase. If automobiles had been mass-produced in 1894, Survival of the Fittest would have made a good bumper sticker.

In Huxley’s era, the concept seemed to make perfect sense. At the time, people knew precious little about animal behavior, and much of what they thought they knew was wrong. Thus, the idea of evolution as a simple drama of endless tooth-and-nail, dog-eat-dog competition seemed to explain everything . . . except, of course, for the observed data about a species people did know something about, which was the human one. Among humans, as anyone could see, an evolutionary-style competition occurred in many consistent and impressive ways, and Huxley’s brand of Darwin’s idea helped explain that. At the same time, however, there was that other side of human behavior—the side where we find people being helpful, thoughtful, generous, cooperative, and altogether seemingly noncompetitive indeed. How could this new theory of evolution explain any of the observed data about the cooperative and caring side of human existence?

The answer, according to Huxley, was that it could not. Evolution explained only the nasty, competitive side of the human world. Therefore, so his logic proceeded, one must assume that morality—a cohesive force that supposedly creates cooperation and an altruistic style of spontaneous kindness—could only be attributed to culture. Nothing to do with evolution. Completely separate from the springs and cogs of our natural machinery. And thus the matter was settled. Or so it seemed. Humans, Huxley would conclude, were the only beings on the planet capable of restraining the inborn viciousness derived from endless competition that supposedly characterizes all other life. Even the famous British ethologist Richard Dawkins would insist, in the opening salvo of his best seller The Selfish Gene (1976), that those who wish to “build a society in which individuals cooperate generously and unselfishly towards a common good” can “expect little help from biological nature.” He went on to issue a plea: “Let us understand what our own selfish genes are up to, because we may then at least have the chance to upset their designs, something that no other species has ever aspired to.”

Darwin would not have agreed. He understood that humans were fundamentally a part of nature, which meant in turn that one could anticipate a deep evolutionary continuity between humans and nonhumans. And he surely would not have been surprised by the account of Kuni’s tender ministrations to the injured starling, since he always entertained the idea that animals could have positive, pro-social inclinations comparable to those of humans. As he noted in The Descent of Man (1871), “Besides love and sympathy, animals exhibit other qualities connected with the social instincts, which in us would be called moral.”

Still, Huxley’s concept of evolution as nothing but a wild and endless battle for survival of the fittest became the popular one, while biologists quietly struggled with the problems of cooperation and kindness—qualities they were increasingly to find in the natural world, particularly after the mid-twentieth-century explosion in animal observations. Cooperation and kindness among animals are “problems” because, indeed, an evolutionary theory based on the idea of endless competition does not immediately explain such seemingly noncompetitive behaviors.

Nevertheless, even as early as the 1930s, theorists had begun to identify the evolutionary logic of various sorts of cooperation. First came the idea of mutualism—a form of cooperation that provides a competitive edge by giving two or more cooperating organisms immediate benefits. Three cheetahs come together to kill a prey animal too big or quick for any of them to kill alone. Later came the notion of nepotism—a style of cooperation that can be understood as competition at the level of one’s genes. A squirrel risks her life to warn her kin about the approach of a fox; she may lose her life in the process, but she may also win the evolutionary competition if enough of her genetic package, carried by her surviving offspring and siblings, comes to define the next generation. And, finally, there emerged the concept of reciprocity—a style of cooperation that resembles the workings of an economic marketplace. Chimpanzee A grooms Chimpanzee B today, thereby reinforcing an alliance that leads B to support A in a fight against Chimpanzee C tomorrow.

Those three ideas explain how evolution as competition can still produce remarkable, regular, and common instances of cooperation. They explain why animals routinely cooperate in hunting, sharing food, huddling together against bad weather, taking turns to watch out for danger, forming defensive or offensive groups against a predator, sharing in the care and nursing of their young, adopting helpless orphans, and so on.

Yet cooperation is not the same as kindness—and the act of spontaneous kindness I described at the start, where Kuni the bonobo tried to rescue, protect, and help an injured starling, would appear to be a different sort of behavior altogether. For each of three kinds of cooperation—mutualism, nepotism, and reciprocity—the cooperators can hope to get something out of their actions. Kindness toward an injured bird, by contrast, may seem completely gratuitous. We might imagine that Kuni risked his life climbing that tree, and we can conclude that he wasted his time and energy doing something for a creature who is not a relative and who can never return the favor.

Kindness—or pure altruism, as some biologists call it—appears to be an odd sort of behavior among animals, and yet it is probably a lot more common than most people imagine. Rats may be capable of it, if we take seriously a classic experiment originally reported in 1959. In this study, scientists caused some albino laboratory rats to feel uncomfortable or distressed by wrapping them in tiny corset-style harnesses, with their legs free to move, and then hoisting them off the ground using an Erector-set motor. The rats would respond by squealing and wriggling madly. Twenty other rats were then, one by one, placed in an adjacent compartment and allowed to watch the distressed rat through a transparent window for ten minutes. Pressing a bar in their compartment gave the onlooking rats the option of lowering the suspended rats, and even without any training, they consistently pressed it. For comparison, another twenty rats were put in the same situation, except that instead of a suspended fellow rat, they watched a suspended block of Styrofoam. These rats occasionally pressed on the bar as well, but far less often. Watching a fellow rat in distress, then, moved laboratory rats to engage in rat-sized acts of kindness.

More recently, the research psychologist Jules Masserman and his team at Northwestern University demonstrated that rhesus monkeys, too, will sometimes act to lessen the suffering of other monkeys. Fifteen of them were placed in a compartment with a one-way window through which they could see into an adjacent compartment where another monkey was feeding. They were taught to acquire food treats by pulling one of two chains, either of which would deliver the same amount of food. Then, on the fourth day of the experiment, an electric grid lining the adjacent compartment was activated, so that whenever a watching monkey pulled the first of the two chains, the other monkey would receive a shock. Pulling on the second chain delivered no shock. Ten of the fifteen monkeys quickly developed a significant preference for pulling on the chain that did not shock the other monkey, while two more stopped pulling on either chain, one for five days, the other for twelve. Those two actually chose to endure hunger and the threat of starvation rather than shock a fellow monkey.

Such experiments on the helping behavior of animals in captivity are being supplemented by observations in the wild. For example, the Boston University biologist Thomas Kunz, watching fruit bats in Florida, noted that a female about to give birth was suspended by her feet, with her head down—a position that would have to be reversed in order to push out her infant. To Kunz’s surprise, another female, unrelated to the first, arrived to correct the situation. She landed next to the pregnant bat and assumed the proper birthing position. It looked like a demonstration, Kunz thought, and indeed the pregnant female seemed to respond. She reversed position, ready now to give birth. Next, the helping bat began licking the mother’s perineum, as if to promote the process. And finally, when the baby bat was born, the helper stroked and groomed it, then appeared to guide the newborn toward the mother’s lactating breasts.

A far more detailed account of animal kindness comes to us from the Cornell University bioacoustician and elephant expert Katy Payne and other scientists, who in June of 2000 were sitting on a platform at a forest clearing in the Dzanga-Sangha Forest Reserve of the Central African Republic, watching elephants. The animals would emerge from the forest for their regular visits to the mineral-rich mud wallows of the clearing. One day, a young elephant, weak from malnutrition, collapsed off to one side of the narrow, sandy trail leading to the clearing. She lost consciousness and within a few hours died, and her collapse and death were witnessed by her mother and older sister. The scientists on the platform also observed the event. Then, using a video camera with telescopic lens, they documented the reactions of a large number of elephants as they rambled along the trail to and from the clearing. In that fashion, the scientists acquired an extensive record of elephant behavior in response to a dying fellow elephant (on day one) and a dead fellow elephant (on day two). In total, the elephants paid 129 visits to the fallen animal.

Most of those visits began as you might expect: with investigation, exploration, sniffing the body, gently touching it, and so on. What next? About 50 percent of the visits ended with a response of fear or avoidance: backing off, sidling away, or dashing off. That’s not surprising, since the presence of a stricken elephant in a place frequented by elephant poachers can signal danger. One elephant, a notorious misfit, reacted aggressively, stabbing the body with her tusks. But on a third of the visits the elephants showed neither fear nor aggression but helping behavior. In roughly half of those cases, an elephant tried to protect the dying or dead animal from others. In the other half of helping cases, the visitor actually tried to rescue the fallen elephant—for example, using feet, trunk, and tusks in an effort to raise her back up again.

Other researchers had already watched these elephants for years, identifying individuals and charting familial and social relationships. Examining this earlier data, Payne and her colleagues found no clear correlation between how individuals reacted and their relationship to the unfortunate elephant. Strangers were as likely to try defending her, or rescuing her, as relatives or close acquaintances were. This, then, seemed a case where none of the evolutionary logic of cooperation applies. It was a case of spontaneous kindness: elephants trying to defend or assist a fellow creature in trouble, without a nepotistic bias or the anticipation of a reciprocal benefit.

It also provides an intriguing animal counterpart to the biblical parable of the Good Samaritan. To refresh your memory: A man traveling on the road between Jerusalem and Jericho is set upon by robbers, who take all he has, strip him of his clothes, and leave him to die alongside the road. As the man lies there, helpless, bleeding, naked, dying, three travelers come upon him. Two are seemingly respectable men, well established members of the same society Jesus was addressing as he told the story. These two men notice the dying man, but—perhaps appropriately fearful of thieves in this lonely place—they cross to the other side of the road and hurry along. That is a logical response, one that you and I can identify with. It’s dangerous there.

How remarkable, then, was the response of the third traveler, who happened to be a Samaritan, a member of that despised and distrusted set of apostate Jews who had developed their own version of the Torah. What would a Samaritan know about goodness or kindness or personal ethics? When this man saw the robbers’ victim, however, he stopped and attended to him. He washed the man’s wounds, wrapped them with bandages, and then placed the man onto the back of his own pack animal and transported him to a nearby inn. The Good Samaritan paid for the victim’s lodging and, upon leaving the next day, placed two silver coins in the hands of the innkeeper to pay for the victim’s care and promised to pay for any additional charges when he returned.

This didactic tale provokes us to consider our duty to our neighbor. Our duty is to behave not like the two respectable men who, apparently fearful, reacted to the dying man with avoidance. No, our duty is to emulate the Samaritan, who embodied a central Christian teaching, which is to practice radical kindness—to love one’s neighbor as oneself.

People often think of human morality as received—either handed down by a wise deity, or inculcated through the workings of culture. But the Good Samaritan story does not suggest that the unusually kind traveler had received a code of ethics that the two other travelers had not been exposed to. Rather it suggests that the Samaritan resisted his own internal impulse of fear in order to follow a second internal impulse that—in my modern English translation of the story—is called compassion. All three men may already have possessed both fear and compassion. Two of them found their compassion overcome by fear, while the third overcame his fear in order to respond compassionately.

This imagined situation can help explain the differing behaviors exhibited by those elephants who, walking along the Dzanga-Sangha trail one summer day, discovered a fellow elephant in trouble. Most of them did the sensible thing, which was to respond cautiously and move away. Some of them did the less sensible thing, which was to ignore or suppress their fear and respond with compassion.

The idea that elephants can experience compassion will not surprise most elephant experts, nor will it shock many experts in animal cognition and behavior, though they might substitute the term empathy. They would also recognize that empathy could underlie the behavior known as pure altruism, or kindness.

The idea is reasonable, but it doesn’t explain how evolution could have produced either the behavior or the emotion behind it. Let me give an example that illustrates this logical problem. In considering behavior from an evolutionary perspective, we think in terms of reproductive success—the movement of genes from one generation to another. But this perspective seems to make altruism a loser’s strategy. Yes, it’s admirable, inspiring. We honor the woman who sacrificed her life so that another human being, a perfect stranger, might live. But the woman who sacrificed her life has also sacrificed her genetic future. Any genes she possessed that are associated with such behavior have not moved as fully as they might into the next generation. Over time, wouldn’t the infinitely patient winnowing of evolution simply cast away all genes associated with self-sacrifice? And why should such genes be there in the first place? How does the competition of evolution even begin to explain a heroic act done for a nonrelative?

One possible answer to this conundrum is to imagine the woman’s self-sacrificial altruism as an extraordinary consequence of a set of genes that is ordinarily useful. It could be that for every person who has died a hero, another dozen equally altruistic individuals have survived and found their social and economic status usefully elevated as a result of their heroism. In addition, the very genes associated with high-risk behavior and high levels of compassion might make a person engaging and dramatic, and hence reproductively successful.

A more intriguing answer has recently been proposed by Frans de Waal, the distinguished primatologist who wrote about Kuni and the starling, and Stephanie Preston, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Michigan. The Preston and de Waal model avoids treating altruism (or “helping behavior”) and empathy as isolated phenomena. Instead, their model would combine helping behavior with empathy, perceptual and emotional contagion (as when a yawn spreads through the entire classroom, or when the crying of a day-old infant sets off a symphony of crying and distress in the entire nursery), and a few similar phenomena into a unified whole. Each element of this whole is, or could be, the product of a single empathetic neural system. The discovery in recent years of specialized brain cells known as mirror neurons—cells that seem to automate an individual’s perceptual and emotional response to many kinds of social stimuli—only strengthens the case for a dedicated empathetic system across animal species.

Looking at the problem this way changes the nature of the question. One no longer asks, How did empathy or altruism evolve? One asks, How did the neural system that supports empathy, altruism, perceptual contagion, and similar phenomena evolve?

Once we see empathy and altruism as part of a larger whole, we are also prepared to recognize the benefits provided by the full system. For example, the system may make mothers instantly and automatically—contagiously—responsive to the needs and actions of their infants. It may allow many members of a social group to benefit from the alert senses of a single individual, through contagious processes transforming a group of ten individual animals, each with only two eyes, into a coherent living entity with twenty eyes. It would help coordinate group actions quickly and automatically, thereby improving any individual’s chances of survival from predators and increasing an individual’s harvest of prey.

As a daily event in the lives of humans, meanwhile, empathy emerges as a continuous series of small and unexpected acts of kindness done without expectation of recompense. In this way, empathy serves its most important social function, as an expressive, positive, cohesive force that connects one person to another.

This article is based largely on material in the author’s forthcoming book, The Moral Lives of Animals (Bloomsbury Press, March 2011).

DALE PETERSON teaches freshman English at Tufts. He is the author of sixteen books, translated into nine languages, many distinguished as Best Book of the Year by the Boston Globe, Denver Post, Discover, The Economist, and other publications. Two volumes, Visions of Caliban: On Chimpanzees and People, coauthored with Jane Goodall, and Jane Goodall: The Woman Who Redefined Man, were listed as Notable Books of the Year by the New York Times.