|

|

||||||||||||||

| features Make Art, Not War Amour in Amherst The Night Ferry Mountains Beyond Mountains think tankplanet tufts newswire the big day departments |

Amour in Amherst

A SCHOLAR SHARES IN THE PAIN OF BYGONE LOVERSAt the turn of the twentieth century, there was one place to go if you wanted to connect with your dearly departed: the hamlet of Lily Dale, in upstate New York. By this time there were perhaps a million professed Spiritualists in America, with more than seventy newspapers and other vehicles for spreading word of their activities. Lily Dale, organized in 1879, had become the epicenter of the movement. Within its confines, occultism was literally a cottage industry, with house after house owned by mediums who would guarantee visitors a link to the other side.

In 1904, a somewhat skeptical Mabel Loomis Todd traveled there. “It did not sound attractive to me as a place, only as a curiosity,” she wrote in her journal. “The whole thing seemed to me pitifully cheap.” But in truth, she was hoping to connect with the love of her life, who had died nine years earlier. After two weeks, during which she attended countless sťances that she derided as fraudulent, Mabel experienced one session convincing enough to shake her to her core.

“How, supposing he had desired to cheat me,” she wrote of the medium, “could he have known that it was Austin, and Austin alone I desired? And if by any . . . chicanery he could have found out his name in the few hours between his arrival in Lily Dale and my coming to him, how could he have known that the middle name was the one I called him by? And how could he have imitated that voice! And said the characteristic things with certain reiterated words just as Austin did! . . . It was wonderful to stupefaction.” The encounter, she claimed, “tore my heart strings so that for weeks I walked in a daze. The voice was identical with what I had so longed for nine years to hear. . . . But what does it mean?”*

Mabel Loomis Todd (1856–1932) was a rare nineteenth-century female public intellectual, traveling the world and publishing books and articles on an astonishing array of topics, from eclipses of the sun to witchcraft in New England. She was a gifted musician, widely known as an excellent soprano and the most accomplished pianist in Amherst, Massachusetts, an artist whose paintings of flowers and butterflies adorned the walls of many friendsí homes, and a sought-after speaker. Today, she is remembered principally because she was the first editor of Emily Dickinsonís poetry, which she and her coeditor, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, published in 1890. But another notable facet of her life is what brought her to Lily Dale: for thirteen years, she had a romantic relationship with the poetís brother, William Austin Dickinson, when both were married to other people. Perhaps because Austin was the scion of the venerable Dickinson family and a leading citizen of Amherst—he served as treasurer of Amherst College and thus signed the paychecks of Mabelís husband, David Peck Todd, a professor of astronomy—neither legal spouse seemed to make a public issue of the illicit relationship. But they both knew of it. Indeed, it was the dirty little secret that everyone in the small college town seemed to know.

I first learned of this relationship through my research for a dual biography of Mabel and her only child, the equally accomplished Millicent Todd Bingham (1880–1968). Millicent was the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in geography from Harvard. A talented linguist who translated works from French to English, she was also an excellent violinist and an author of articles and books on geography and family history.

One other remarkable thing about both mother and daughter was that they never threw out a single scrap of paper. The result is the voluminous Mabel Loomis Todd Papers, a collection at Yale University Library that has proved invaluable for my work. It includes thousands of pictures, multiple journals, and dozens of scrapbooks filled with calling cards, clippings, programs, and more. Much more. Mabel and Millicent were dedicated diarists, too, writing every day from middle childhood until the eve of their respective deaths, and they freely expressed themselves in letters, hundreds of which survive. More than four hundred boxes of such material are housed in the basement of Yaleís Sterling Library.

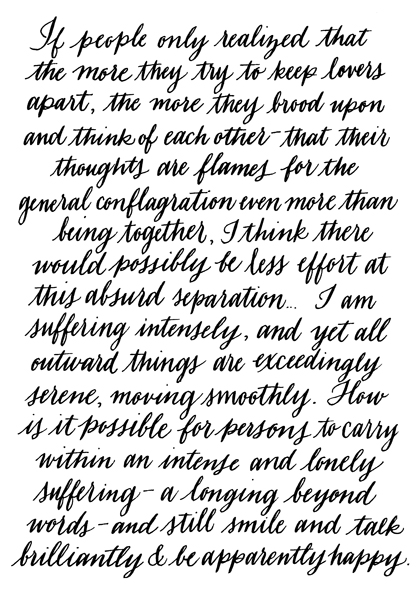

Among the documents are the love letters that Austin and Mabel wrote to each other over more than a decade. Although the couple lived but a half mile apart and saw one another with some frequency, they often passed letters to each other through other people, in between piles of papers or inside folded newspapers exchanged on the street. Mabel sometimes carried letters to Austin pinned inside her bodice until she had the opportunity to slip them to him.

|

| Mabel to Austin, October 9, 1884 |

The relationship, whose outlines emerge through these letters, and through diaries and other gleanings from the mountains of paper Mabel and Millicent left behind, began innocently enough. Mabel met Austin in 1881 when her husband, David, returned to teach at his alma mater. Coming from cosmopolitan Washington, D.C., she had reservations about life in a small New England college town. But they melted away when she met Austin and Sue Dickinson, patrons of the arts, leaders of civic endeavors, and Amherstís most prominent citizens. Austinís odd sister, Emily, who lived next door to Austin and Sue, only added to the Dickinsonsí appeal. Emily rarely emerged from her room but occasionally sent friends like Mabel snippets of the most intriguing poetry.

Mabel eagerly accepted the Dickinsonsí many invitations to soirees and concerts, games of whist and sleigh rides. She always wanted to be “brilliant,” in her words, and her association with the Dickinsons provided her with new opportunities to shine. Within a few months, she established a more personal relationship with Austin Dickinson. She found that he spurred her to aspire to greater and greater things, to think of herself as someone more than sheíd ever been. Austin was highly educated, and like Mabel, he was passionate about ideas and nature. He was also profoundly disappointed in his marriage and his children, whom he viewed as socially ambitious but lacking the substance, intellect, and vibrancy he found in Mabel.

In the fall of 1882, Mabel and Austin admitted their love for each other. Nothing would ever be the same. They considered each other to be their true spouse. Mabel switched her wedding ring to her right hand and wore the one that Austin gave her on her left. Still, the affair, which was unfolding in a provincial town steeped in traditional nineteenth-century New England values, brought its sorrows. While David Todd appears to have accepted Mabel and Austinís relationship and enabled it in many ways, Sue Dickinson was not so forgiving. She cut Mabel off from the social activities over which she had control and made certain that others in Amherst did as well. Mabel increasingly felt shunned, and often referred to herself in her private writings as “a martyr.”

Although Austin was twenty-seven years her senior and deeply rooted in the town in which he had been born and raised, he traveled west in the late 1880s, perhaps to seek out an opportunity with Mabel to start over. But they remained in Amherst. For both of them, this meant that their transcendent love was marred by the most indelible frustration. Their predicament also strained Mabelís relationship with her daughter. Young Millicent could not understand why her mother so often went out for long carriage rides with the austere Mr. Dickinson, or why she heard bits of hushed talk about her mother on the streets, or why her mother frequently refused to attend church.

From the start, mother and daughter shared a bond that was close but complicated. Mabel often outsourced Millicentís care to her parents, so much so that the girl ended up spending months at a time with her grandparents in Washington, D.C. And when she was back in Amherst, she had to contend with a mother who seemed to flout convention at every opportunity. She was upset when she realized that other peopleís mothers cooked for their families, while her own mother rarely set foot in the kitchen. Though they shared interests in music, literature, and nature, Mabel and Millicent had very different sensibilities. As she matured, Millicent let her Puritan roots and morality guide her own life, and she disapproved of Mabelís proclivity for fashionable clothes and reputation as the best dancer, over whom the college boys jockeyed for a place on her dance card.

But even though Mabel often seemed to ignore Millicentís needs, she was encouraging to her daughter and intensely proud of her achievements. Mabel nursed Millicent through many debilitating illnesses and read to her when she was sick, even as an adult. In turn, Millicent, who found so much about her mother puzzling or even objectionable, was unstintingly loyal to her. She jettisoned her own career in the late 1920s when Mabel asked her to help bring out a new edition of Emily Dickinsonís poetry, and she then became, like her mother, an expert on the idiosyncratic style of the Amherst poet. Just as significantly, the driving force behind the final two decades of Millicentís life was her quest to shape and preserve her motherís legacy, as well as her own.

In fact, Millicentís careful archiving may be why perusing the Mabel Loomis Todd Papers has sometimes been like immersing myself in another world. As Iíve read through Mabel and Millicentís diaries day to day, I have heard their whispers in my ear. Feeling part historian and part voyeur, I, like Mabel at Lily Dale, have sometimes felt overwhelmed with the sense of having made contact with those long dead.

I, of course, have the benefit of the biographerís omniscience. It has enabled me to know things about my subjects before they realized what was happening in their own lives. There was the time in 1879, for example, when a series of diary entries found Mabel complaining of indigestion and fatigue. She didnít understand what ailed her, but I did—because I knew that in February of 1880 she would give birth to Millicent. Similarly, when Mabel first came to Amherst in 1881 and remarked in her diary about meeting the “charming Dickinsons,” I was far more aware than she of how auspicious a moment that was.

My research on the next thirteen years—the years of Mabel and Austinís relationship—was replete with these kinds of moments for me. The diary and journal entries that document the coupleís carriage rides into the Pelham hills, their conversations about nature or books, and their sex life transported me inside the heads and hearts of these nineteenth-century paramours. So did their letters. “Written words alone are too insufficient now,” read one missive, penned by Mabel. “We have come too near together. We want . . . the wild life current to throb back and forth from one to the other with its subtle messages . . . we stand just before the veil of closest intimacy.”

Austin was equally ardent. In one of his letters to Mabel, he wrote:

Is it not better, and enough, for me to say simply, what I have said so many times before, that I love you, love you, love you with all my mind and heart and strength, and that I know what I mean when I say this, that with you my real life began! That with you I have found what life may mean . . . that in you I have found my perfect soul-mate, for time and eternity. That in you I have found my longing satisfied. . . . That I thank God for you every hour. . . . No words can express, dearie, the depth and strength of my love for you, its sacredness, its holiness.

As I took in such passages, I knew better than either of the lovers that the pseudo-religious fervor was setting the tone for how they would justify their relationship in defiance of nineteenth-century mores. And when Mabel wrote to Austin, “Why should I and why shouldnít I! Who made and rules the human heart! Where is the wrong in preferring sunshine to shadow?” I realized, though she had no clue, that she was introducing themes she would echo her entire life.

Mabel and Austinís relationship was filled with the recognition that in each other they had found an intellectual equal, one who met their every physical, emotional, and spiritual need. Over and over, they offered soaring odes to the love they considered so lofty that no one else could possibly understand or match it. Yet Mabel did not conceal the pain she endured. On the morning of their seventh Thanksgiving apart, in 1888, she wrote to Austin:

That standing-aside-and-looking-on sort of feeling that I have always had used to hurt me and make me very lonely. I am used to it by now. . . . But I see the world slipping from me—I see it becoming daily more impossible for me to live in the little town which is yours. I see myself more and more alone. . . . I see power over all this lying idly in your hands, and you the only person able to cope with this terrible thing.

After all these travails, Mabel had to face Austinís mortality. One of the most troubling moments Iíve had since I began my research came when I was reading her diaries on microfilm in Tuftsí Tisch Library. I was up to the summer of 1895, and Austin was getting progressively more ill, his heart diseased and weakening. I knew what was coming. Mabel, alternating between hope and fear, recorded in her diary each day how Austin said he had slept, and what he had been able to eat. On August 6, 1895, she wrote, “My darling is much better. . . . I solemnly thank God.” Soon, though, her entries grew frantic. “My heart cries out to be with him!” she entreated, and added time and again that she would gladly give up her own life if only—if only—Austin would be well.

As I sat there, reading how she sought advice from a faith healer and a palm reader when the cardiologist dispatched from Boston offered no hope, I wanted to prepare her for the inevitable. I wanted to tell her to be strong, and tell him to hurry and make good on all that he had promised her. Nonetheless, when death came for Austin, on August 16, 1895, as I knew full well it would, I found myself still unprepared.

“Where is my zest and enthusiasm?” Mabel lamented in one of a series of aching elegies I could hardly bear to read. “Austin has carried them with him. I love him most terribly, o heart, soul, mind, body. I know we shall be together again, before very long. But o! Dear Austin!” As the tears streamed down my face, one of the librarians came over and asked if I was okay. “Austin died!” I blurted out. It was all I could manage.

I left Tisch that day stunned, feeling much as Mabel must have when, by her own account, she “walked in a daze” after hearing Austinís voice channeled by a medium in that small town in upstate New York. I remember being startled to see the snow on the Hill—startled because I was lost in an August of more than a century ago.

Julie Dobrow, Ph.D., has taught at Tufts for eighteen years and serves as director of the Communications and Media Studies Program. She is currently writing a dual biography on the extraordinary lives of Mabel Loomis Todd and Millicent Todd Bingham.

*All quotations from the letters, diaries, and journals of Mabel Loomis Todd and William Austin Dickinson are collected in the Mabel Loomis Todd papers, manuscripts and archives, Yale University library.