|

|

||||||||||||||

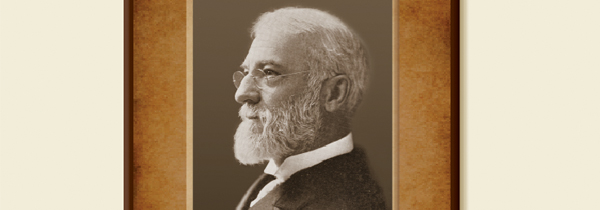

Edwin Ginn and the Case for Peace

The publishing magnate, Class of 1862, fervently believed that reason would prevail over warArriving in a special car attached to the 7:44 p.m. train from Boston, the guests gathered around the piano in the music room of Edwin Ginn’s sumptuous Winchester home on Valentine’s Day, 1908. The occasion marked the seventieth birthday of the man with whom many had worked for decades at Ginn & Company, one of the nation’s three largest textbook publishers. The celebrants presented the bearded, bespectacled Ginn with an engraved silver plate and other gifts, including a hand-lettered illustrated card “laid out in a red morocco portfolio” and made at the bindery of his Athenaeum Press, according to the evening’s program. They recited poetry to him as well, tracing his life’s arc from its “small beginnings” in rural Maine to Tufts College, from which he managed to graduate in 1862 despite failing eyesight, to the “day you tried your luck at schoolbook selling; in consequence, forever hence your bank account was swelling.”

Only briefly did the verse note the passion that by then was consuming the life, work, and much of the fortune of Edwin Ginn:

Meanwhile you share this growing care

And partners now surround you;

But with release the dove of peace

Now hovers close around you.

Though he came to the cause only late in life, Ginn was convinced that

global peace was within human reach. The key, as he saw it, was education.

Once properly informed by the schools, a responsible press, and enlightened

leaders, the public would come to realize the folly of war and militarism. “It

is for us not only to institute the measures necessary to curtail this

awful waste of life and property, but to bring conviction to the masses

that this question cannot be handled successfully by a few people,” he

wrote in a 1912 pamphlet discussing the World Peace Foundation, which he

had founded two years earlier. “It is a work, a most difficult work,

for the whole world.” He would pursue that difficult, quixotic work

until his death on January 21, 1914, weeks after suffering a stroke.

In some ways Ginn was “very much of his era,” says Robert

Rotberg, a former Tufts academic vice president who now presides over the

World Peace Foundation, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and directs a program

on conflict resolution at Harvard. At the end of the nineteenth century,

many distinguished Bostonians were discussing how to advance international

law over conflict, he notes in his book A Leadership

for Peace: How Edwin Ginn Tried to Change the World. Among the most prolific and powerful voices

of the city and era was the Reverend Edward Everett Hale, a physically

and otherwise imposing abolitionist and preacher for peace who in 1889

proposed a permanent international tribunal. This court, to be accorded “the

honor and respect of the world,” would settle disputes without bloodshed

and, he predicted, “mark the great victory of the twentieth century.” Hale’s

frequent calls for the world to advance arbitration over warfare clearly

resonated with Ginn.

Nor was Ginn the only prominent businessman pursuing the cause of world peace. Andrew Carnegie and others were doing the same. Rotberg maintains, however, that “Ginn stands out enormously because his point of view was not a pacifist’s one”—justified purely on moral grounds—“but one that war made no sense, that it flew in the face of rationality. Ginn fully believed that a world court and world peace were achievable and disarmament was possible.”

Today, almost 150 years after his graduation—and a century after he served as an overseer and then as a university trustee—Edwin Ginn is still a presence at Tufts. The annals of his World Peace Foundation fill nearly sixty linear feet of shelf space at the Digital Collection and Archives in Tisch Library. The Edwin Ginn Library at the Fletcher School memorializes this extraordinary idealist, a man whose Kantian faith in the corrective power of an inherently rational citizenry never flagged, even on the threshold of World War I.

That Edwin Ginn would end up rich, successful, and sought after in Boston parlor rooms and at international peace gatherings was hardly inevitable for a slight boy born in 1838 on an isolated farm in Orland, Maine. His early life was, as he recalled in an April 1906 piece in The Tufts College Graduate, “blessed with poverty” and rooted in Yankee practicality. In fact, the man who would eventually publish many of America’s first school primers often had to use birch bark for paper. “My school privileges were very limited, about two months in summer and the same in winter,” he wrote.

[S]chools in those days were appreciated by the lads and lassies, if for no other reason than an agreeable change from the hard work at home—doing chores, milking the cows, piling up the rocks in the fields, weeding the vegetables, and working in the hay-field. Some of us, however, had a real thirst for knowledge, which was not lessened because of the meager opportunities for acquiring it. I think if every boy and girl could have the benefit of the lessons learned on a farm they would make better men and women. . . . Most boys and girls [today] turn away from manual labor as irksome and are too young to realize the part it plays in the building up of character.

At thirteen, Ginn went to work in a remote logging camp, where he cooked for the lumberjacks. A year later, he began to spend months at a time at sea, working in the galley of a fishing schooner. His long turns on deck became occasions for “deep thought, with no living thing to disturb one’s meditation.” Throughout his teenage years, he continued to balance occasional classes with farmwork and voyages to the Grand Banks. Because his local school did not teach Latin, a prerequisite for college, Ginn, at sixteen, began to walk more than two miles each way, every day, to a seminary in Bucksport. He completed his secondary education as a boarder at Westbrook Seminary, run by the Universalist Church, and he briefly considered becoming a minister. His pivotal turn toward a career in business occurred during his days as a struggling college student. As he recounted in the Graduate article:

For a time after I entered Tufts I was obliged to board myself on a dollar a week. That seemed hard, but I think I am the better for it now. My room was very meagerly furnished. I could almost count upon my back the number of slats in the bed I slept on for there was but one husk mattress between them andme. . . . In the midst of my college course my health broke down; my eyes gave out and I was advised to leave for a year or two, but when I told my professors that if I left I should never return, they kindly consented to allow me to go on. My classmates read my lessons to me and I graduated with the rest of my class. Because of the trouble with my eyes, my life-work was necessarily changed from a purely literary one. Perhaps to business, semi-literary in its character, probably wisely.

Wisely indeed. The studious Ginn, saddled with debt after graduation, worked as a salesman for a local textbook company, showing both persistence and creativity. At a time when most book salesmen worked through agents, he pursued the alternative approach of speaking directly to teachers and school administrators. He had “an abiding faith in scholarship,” his longtime friend George Lyman Kittredge, a professor of English at Harvard, recalled at Ginn’s memorial service in 1914. “Think what it meant to scholars, big and little, to come into contact with . . . Ginn, who was not only full of life, but believed in them, and could persuade them that their learning was no mere private pleasure of their own, but a possession of actual use to the community.”

In 1865, Ginn, initially with his brother, formed his own firm, publishing primers as well as books in Greek, Latin, and other languages. Texts stamped with the Ginn & Company logo soon lay next to inkwells on desks across the nation. Ginn kept breaking new ground: while other publishers had little interest in producing music texts for young students, for example, Ginn saw both an educational need and a business opportunity. Ginn & Company music books consequently became staples for generations of lesson takers.

Ginn’s own love of learning also remained robust, despite failing eyesight that made reading arduous. His first wife, Clara Eaton Glover, one of twenty-four women to graduate Vassar College in 1868, came to his aid: she not only cared for their four children and helped him with his business, but until her death in 1890, she also read aloud to him for hours every evening.

Ginn the businessman had an inclination toward public service, declaring his company’s goal “to influence the world for good by putting the best books into the hands of school children.” The Reverend Hale impressed a general sense of noblesse oblige upon well-to-do Bostonians. “We professional men,” he exhorted in 1871, “must serve the world, not, like the handicraftsman, for a price accurately representing the work done, but as those who deal with infinite values, and confer benefits as freely and nobly as nature.”

But evidence of Ginn’s commitment to specific social causes is scant. “We know that he hobnobbed with Harvard’s thinking classes and the bright social reformers of Boston,” says Rotberg, “but not precisely how he was influenced, or how he sought to exert the power that he came to wield as a prosperous corporate leader.” He remained a man of hardscrabble Maine: no-nonsense, teetotaling, and taciturn.

Then, in 1893, came Ginn’s second marriage, at age fifty-five, to thirty-year-old Marguerita Francesca Grebe, a violinist he had met while attending a concert at a summer artists’ colony in New Hampshire. She opened the publisher’s eyes to new cultural horizons and exposed him to social causes that appealed to her generation, such as housing for the poor. In 1901, he purchased land along the Charles River to build Charlesbank Homes, a model tenement for working women that would today be called affordable housing. And the once avid hunter and fisherman became a vegetarian. “There will . . . come a time when the killing of animals for food will be regarded as . . . uncivilized and cruel,” Ginn said in a 1909 newspaper interview.

More significantly, after marrying Grebe, Ginn began devoting his talents to the world peace movement. In this he was clearly influenced by the intellectual giants among whom he moved, especially Hale. Through the first decade of the twentieth century, as European nations armed for war, he traveled to peace gatherings at The Hague and elsewhere, urging acceptance of world courts and other international bodies to settle disputes. But he hoped to do more than simply preach to the choir. “No matter how good the speeches made or the books published, they do not reach the public to any great extent and as a general rule come only to the attention of those who need no conversion,” he wrote in a pamphlet aptly titled “Practical Thoughts on Peace.”

Ginn dipped into both his wealth and his pool of creative and practical skills in an effort to bring the subject of peace “so forcefully before each and every one that all will feel that it is necessary to take a hand in it.” Books with titles like The Moral Dangers of War, The Future of War, and War Is Not Inevitable, as well as works by famous peace supporters such as Leo Tolstoy and Immanuel Kant, appeared under the Ginn & Company imprint.

Ginn, the man who made Sanskrit and Shakespeare available in the American classroom, invariably returned to the need for education. He encouraged schools to “impress upon the young minds—those who will soon undertake the world’s work—the true principles which should govern international affairs.” Schoolbooks, he said, should be “carefully examined and everything . . . that would tend to encourage . . . martial spirit should be carefully weeded out.” He even urged mothers to forbid tin soldiers and other martial toys, and warned against the tendency to romanticize warfare:

Is it surprising that our children should receive the impression that war has contributed cardinally to the development of mankind when so large a part of our histories and so much of the literature studied are devoted to details of the battlefield . . . the marshaling of soldiers in glittering armor, stirring music, and brilliant charges—everything to inspire the young to become part of this magnificent display? The other side of the picture should be as carefully portrayed—the return of the regiments reduced to a tenth of their original number, maimed and feeble.

While not all were persuaded—one newspaper editorial dubbed him “mollycoddlish”—Ginn pressed on. In 1909, he proposed a School for Peace that would study the costs of international conflict and seek alternatives to militarism. A year later, the School for Peace became the World Peace Foundation. “Until now men have organized to kill one another,” Ginn said in a newspaper interview about his decision to establish the foundation. “This organization that I propose will aim to keep men from killing each other.” Pragmatism, not pacifism, would be its bedrock, as he explained in a pamphlet:

It is a mistake for the advocates of peace to cry, Disarm! Disarm! without supplying a rational substitute for the present armaments; for the people of the world have been running so many years along the present track that they will not give up what they feel is necessary for the safety of the nations until something else is put in its stead that will in their judgment accomplish the same end at less expense of blood and treasure.

Ginn, who once lamented, “We spend hundreds of millions a year for war; can we afford to spend one million for peace?” reached deeper into his fortune in 1910. Having donated some $10,000 a year to peace efforts, he committed $1 million (nearly $24 million in current dollars) to the World Peace Foundation. The money—about a third of Ginn’s wealth—would fund research, writing, and other efforts to generate support for international peacemaking bodies backed by an international army and navy. Ginn proposed that such a force be funded by contributions from each nation equal to ten percent of their annual military expenditures. The hoped-for product of his investment—global disarmament—would come about within roughly ten years, he speculated.

What came instead, of course, was artillery and poison gas. And a war that did not end all wars. And a League of Nations that failed. And even worse subsequent developments that would seem to make Ginn and his faith in the power of rationality and global federalism seem virtuous but naïve. “Maybe it’s fortunate that he died before he could see the carnage of World War I,” says Rotberg.

Were Ginn to come back today, however, he might not entirely lose heart. Surveying the holdings of his namesake library at Fletcher, for example, he would find documents from the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, the European Court of Justice, and the European Court of Human Rights—organizations that come closer to his vision of an international arbitration body than anything that existed during his lifetime. And he would see that the World Peace Foundation, while not rendered obsolete as he would have hoped, is still working to defuse conflict, funding research on ethnic cleansing, civil wars, licit and illicit arms trading, and a range of other pressing issues, including how to resuscitate failed states.

Not exactly peace in our time. But the pragmatic Edwin Ginn would appreciate such rational steps along his determined path.

A Tisch College senior fellow as well as a contributing writer to CommonWealth magazine, PHIL PRIMACK, A70, is a journalist, editor, and policy analyst whose articles have appeared in the New York Times, the Boston Globe, Columbia Journalism Review, and the Washington Post.